I am not a military person but there’s something to the idea of being ordered to attention. How easy it is to drift through the day and end it none the richer for the experience. Thanks to Anne Lamott (and my friend June Cressy, who sent me this quotation from her), I see how guilty of this I am.

“From the simplest lyric to the most complex novel and densest drama, literature is asking us to pay attention. Pay attention to the frog. Pay attention to the west wind. Pay attention to the boy on the raft, the lady in the tower, the old man on the train. In sum, pay attention to the world and all that dwells therein and thereby learn at last to pay attention to yourself and all that dwells therein.”

The biggest thing I have lost in what has been overall a good, healthy period of not writing a novel, is the level of attentiveness required to find many of the insights and details that work their way into my writing. An overheard comment, a bit of body language, an untied shoe, a puff of breeze can become a central metaphor or just a little detail that makes the book more real and alive.

Instead, I have had a wonderful stretch of time in which I have had nothing on my mind on my walks, in my car, and at workouts except the audiobook I am currently listening to. I take in my surroundings (including the Alcazar Garden in Balboa Park, pictured here, which I walk through every day on my way to and from the college) but not in a contemplative or searching way, a way open to the surprises that always play an important role in shaping a book.

Mostly I haven’t started writing because I haven’t been taken over by a story yet. Maybe all those forgotten women have moved on to populate other writers’ heads. Maybe they know I need a break. Then again, maybe someone is saying, “turn off the audiobook–I’m trying to talk to you.”

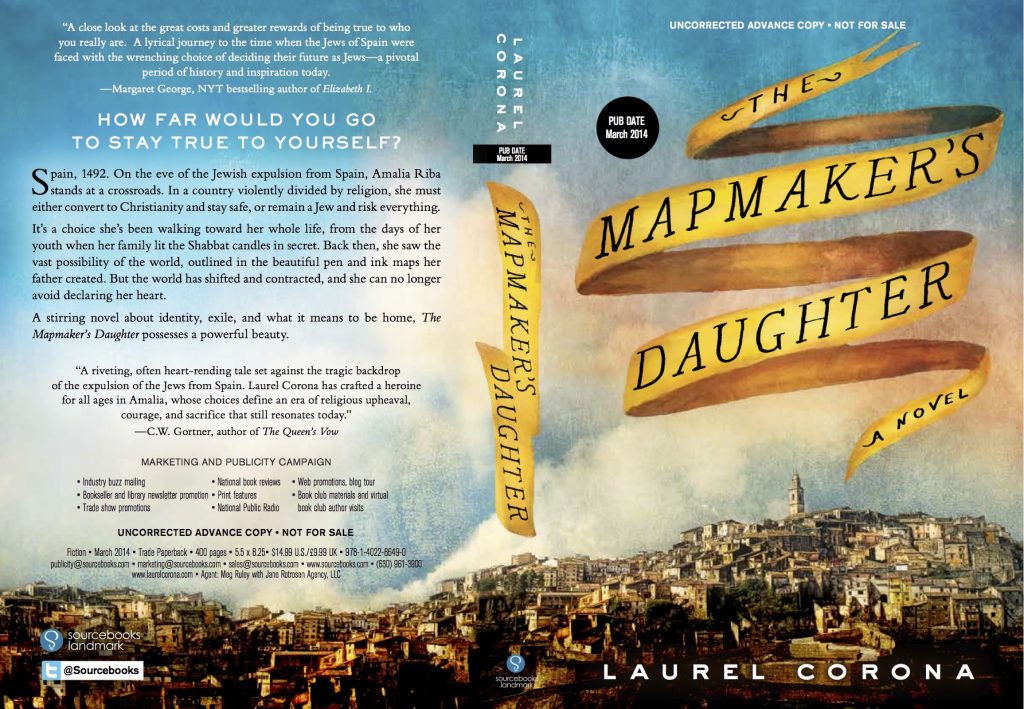

I have written five historical novels, the fourth of which, The Mapmaker’s Daughter, is on the way next March from Sourcebooks. The fifth, The Intuitive, is a completed and fairly well polished draft, but not done to my satisfaction yet. I tell myself that if I don’t write any more historical fiction, that’s okay, because five is a lot, and I’ve made my overall point about forgotten women pretty well by now.

What I miss: the fun of finding out what’s going to happen next as I’m drafting. Also, the great joy of working in the kinds of insights I described above, and the sheer joy of playing with language.

What I don’t miss: the compulsive, all-consuming vortex that writing a book always becomes. I haven’t been able to figure out how to have a full and balanced life, stay in full bloom in my relationships with other people, and avoid the feeling of being a little out of kilter in my teaching, when I am writing a novel.

I haven’t been able to get that nagging idea out of my head that I should be accomplishing something every minute of every day. I have to develop a more inclusive sense of what it means to have something to show for myself, something I am adding to the world. Novels have been so clear in that way.

I’m not ready to retire from this self-appointed job quite yet, but the simplest, monosyllabic way to put what I do understand about myself as a novelist right now is this: I don’t want to go there. Sometime back I gave a workshop and wrote a blog post called “Writing Scared.” I didn’t know I would be in need of my own advice a ways down the road. I guess that means I’m pretty sure another book is coming…someday. And don’t forget, The Mapmaker’s Daughter definitely is. Look for it in March 2014!

Postscript:

In Finding Emilie, here is one way that noticing the details of the day worked into the novel. Fruit flies were hovering over the wine glasses at dinner one night and the next day I wrote this, using them as a metaphor for my heroine, Lili’s conflicted life.:

“Lili?” The voice was Paul-Vincent’s, on her other side. “Aren’t you speaking to me?”

“I’m sorry,” she interrupted. “I’m just a little distracted.”

“I just thought of an excellent experiment. Look at this.” He held up his wine glass. “Do you see?”

“See what?” Not science. Not tonight.

“The fruit flies. They’re everywhere. I think they like wine, but it looks as if something about it makes them act strange.” Lili dutifully held up her own glass trying to catch as much light as possible from the candles. “I’ve got two of them sitting on the rim,” she said, “tipping down inside, like they’re trying to get whatever’s left there.”

In spite of herself, she was interested. “Maybe they just don’t want to fall in.”

“And maybe they’re a little drunk,” he snickered. “I wonder if vapors coming up from the wine are doing that, or if they’re actually drinking. I wish I’d brought the microscope.”

Lili laughed. “You can’t bring a microscope to dinner!”

“I know. But how about tomorrow?” He lowered his voice. “I promise I won’t try to kiss you if you come to the lab.” Lili stared at him, so wrapped up in the problems of the day that it took a moment to understand what he was talking about.

She had already looked at a fruit fly under the microscope and been horrified by its enormous eyes and tiny claw-like feet. Now she felt nothing but sympathy for the little creatures hovering on the rim of her glass. Could they escape or would they just stay there, caught and confused between the forces that attracted and repelled them, until they fell in and drowned, or perhaps flew out and survived a little longer?