When his good friend Gertrude Stein finished reading an early draft of Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms, she handed it to him, saying “Begin again, Ernest. And this time, concentrate.”

Susan Vreeland shared this story during her speech for the San Diego Book Awards earlier this month, and I’ve been mulling it over since then. I suspect that what Stein was reacting to was a falling away from the truth in her friend’s novel.

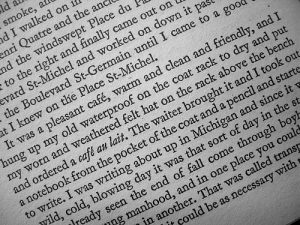

“Truth in fiction?” you might be asking. Consider this beautiful passage from Hemingway’s memoir, A Moveable Feast. “When I was started on a new story and I could not get going, I would sit in front of the fire and squeeze the peel of the little oranges into the edge of the flame and watch the sputter of blue that they made. I would stand and look out over the roofs of Paris and think, ‘Do not worry. You have always written before and you will write now. All you have to do is write one true sentence. Write the truest sentence you know.’ So finally I would write one true sentence, and then go on from there.”

I must admit, I find Hemingway difficult to enjoy. I don’t use his writing as a model because that would be untrue to my own voice, but I love his acknowledgment of the need to be true when I write. Facts are part of this, of course. It’s important not to write anything contrary to what we know the truth to be, but facts don’t convey much in and of themselves. It’s the meaning constructed from them that matters. That is the core of the writer’s craft, whether in fiction or narrative non-fiction, of which Until Our Last Breath is an example.

Where does truth come from? Author Henry James offered excellent advice to new writers when he said, “try to be a person upon whom nothing is lost.” In writing about Jews trapped in the ghetto in Vilna or engaging in acts of sabotage as partisans, I didn’t get all my facts from books. I don’t think the book would have been published if I had. I gathered from my own experience and occasionally from literature (in particular the Bible) the images and sensations that I hope make the book come alive for readers. Going out without a winter coat on the first warm day in spring, the feel and sound of snow crunching underfoot, the rustle of bodies in a crowded room, the softness of another person’s lips, the sweet ache of first love. I am my source for these, for they are things I know.

It takes far more concentration, I’ve found, to write “true sentences” with these kinds of facts than with the ones from books. Susan Vreeland offered as a blessing for writers this verse from Psalm 19: “May the words of my mouth and the meditation of my heart be acceptable in Thy sight.” One doesn’t need to believe in God, or anyone outside the self as the judge of one’s work, to know what this means. As a writer, I have to be real before my books can be.