A novel is a huge undertaking, and for that reason authors are very particular about what subject matter they take on. In thinking about a person, place, event, or era for a book, mere interest is not enough. Something about the topic has to pick you up by the scruff of the neck and refuse to let you down.

That’s what happened to me the first time I watched the segment about Emilie du Châtelet in “Einstein’s Big Idea,” a NOVA program based on David Bodanis’ book E=MC2. Who was this fabulous woman, I wondered, who lived, worked, and thought just as she wished, while navigating the rigid but crumbling world of pre-Revolutionary France? Could she really be as amazing as she seemed?

The answer turned out to be a resounding “yes,” and I knew I wanted to tell the world about her. And then I ended up doing something different. Rather than focus on Emilie’s story, I decided to focus on the baby daughter she left behind when she died at age forty-three. What would it be like to grow up the motherless victim of a scandal that causes her father’s rejection, raised by two women at war about the proper way to educate a young girl? What would it be like never to be told how remarkable her mother was, even though Emilie’s spirit and intelligence shines as brightly in her?

As life in aristocratic society constricts around her like the excruciating corsets she is forced to wear, Emilie’s daughter Lili must learn what the reader already knows–that the secret to understanding herself and gaining the courage to fashion her own life lies in seeking out the story of the remarkable woman who bore her. And who knows? Perhaps in Emilie du Chatelet’s life there is a message for you, the reader as well.

Synopsis

Stanislas-Adélaïde du Châtelet, known as Lili, is a thoughtful and serious girl growing up as the ward of a Parisian noblewoman, Julie de Bercy. Madame de Bercy, a friend of Lili’s dead mother, the brilliant and controversial scientist Emilie du Chatelet, has a daughter, Delphine, the same age as Lili. Though they could hardly be more different, the two girls grow up as sisters, steadfast friends, and confidantes.

Lili can never understand Delphine’s fascination with frivolous things like beautiful dresses, perfect curtsies, and fairytale endings. She wants the world of the mind, a life in pursuit of the truth about nature and people. Instead, she boards with Delphine at a convent school where independent thinking is punished, and she endures excruciating comportment lessons with one of the Châtelet relatives, the prim and judgmental Baronne Lomont. It is clear to Lili that she is expected to be satisfied with having no goals in life other than to be a supportive wife, charming conversationalist, and pious mother.

Home at Maison Bercy with warm and free-thinking Julie, whom both Lili and Delphine call Maman, Lili is encouraged to be herself and use her mind. Julie is one of a small group of salonniéres in Paris, noblewomen who open their homes at certain times each week to artists, writers, and the group of French thinkers known as philosophes. Here Lili is exposed to the radical and revolutionary ideas of people such as famed naturalist George-Louis LeClerc (better known as Comte de Buffon), encyclopedist Denis Diderot, and philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

But Julie cannot indefinitely hold off the pressure to conform to social expectations. In their teens, both Delphine and Lili must prepare for presentation at Versailles, followed quickly by marriage. As the world closes in on Lili, she decides that knowing more than the sketchy details she has been told about her mother’s life may provide her with a better sense of herself. Hoping that this knowledge will help her chart her own future, with Delphine’s loyal help, Lili ventures out to find the people and places central to her mother’s story.

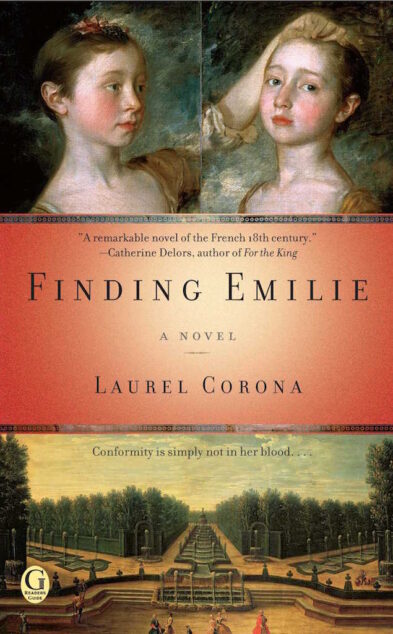

Set in France during the last decades before the French Revolution, FINDING EMILIE explores the complicated tensions between the frivolity of court and the serious pursuit of scientific knowledge, and the perils of being caught between the demand for conformity and the need to release and fulfill one’s genius. Through Lili’s discoveries, Emilie du Châtelet speaks not just to her but to us, about remaining true to ourselves regardless of our circumstances.

Qs & As

Who is emilie du châtelet and how did you become interested in her?

I’m a professor of humanities at San Diego City College, and every one of my novels has come about as a result of having my ears perk up at the mention of forgotten or marginalized women in the past. I first ran across her name because she was Voltaire’s lover but she was never more than a footnote in the discussion.

I’ve always had the impression that noblewomen who were lovers to great men were a starchy lot in their wigs and corsets, so I wasn’t interested in knowing more about her until a book and DVD came out about Einstein’s theory of relativity, in which the author, David Bodanis, credits her as one of the champions of the idea of kinetic energy. The idea that energy is really mass times velocity squared, not just multiplied was quite controversial at the time, because many scientists saw the idea of hidden forces as a remnant of medieval thinking.

It didn’t take me long to discover that Emilie’s personal story and her scientific achievement are both quite amazing. She was an intellect of the highest caliber from a very young age, fluent in a number of languages, and so fascinated by science and math that she used some of her patrimony to hire the best mathematicians and scientists in France to teach her privately. She was also a very sensual creature, and if the tutor was attractive, it appears from time to time there may have been a bonus to the sessions.

Despite her obligations as a noblewoman, she rebelled as best she could against social constraints, believing that the only way to be truly happy was to know who you are and act accordingly. The idea of being your own best friend came naturally to her. She was a voracious reader (she and Voltaire amassed a library that was bigger than in many universities at the time). a gambler, a cross-dresser when she needed to go places only men could go. Probably the single greatest emblem of her individuality was her drawing room at the chateau she shared with Voltaire. It had the usual couches, chairs, and tables, but set in the middle was a bathtub, so Emilie could enjoy a good soak without benefit of more than a chemise, while she and her friends enjoyed great conversation.

But she was more than a pampered, rich aristocrat. How does science fit into her story?

It’s important to note that while she was living this rather self-indulgent life, she was also writing a book called The Elements of Physics, in which she tried to reduce everything about the physical world to a few basic principles, as well as writing a treatise on the nature of light and heat. But her most important project was her translation of Newton’s Principia, which includes the laws of motion and is one of the most important works of science. But to call it a translation is an understatement.

Newton was obsessed with getting credit for his ideas, but not equally obsessed with anyone actually understanding them. The Principia in the original Latin is apparent quite obtuse and he didn’t supply adequate mathematical proofs for his ideas. Emilie was one of the few people who truly understood Newton, and she didn’t translate the Principia from Latin into French so much as rewrite it so others could understand. And she went further, supplying mathematical proofs that she figured out for herself from his conclusions.

Six days after giving birth to a little girl, the result of a torrid affair with an army officer at age forty-three, she put the sealing wax on these mathematical proofs to mail them to the Academy of Science in Paris. A few hours later, she put her hand to her head and said, “I don’t feel well.” That night she died, probably of an embolism. Her work was forgotten for ten years and then finally published. It is still the translation used today in France to teach the Principia.

The daughter she died giving birth to, not emilie herself, is the main character in the novel. Tell us a little about the world Lili lives in, and what her reactions are to it?

I felt very strongly that readers needed to know about this incredible woman, but I didn’t think she could be the main character for two reasons. First, I knew readers would love Emilie as much as I do, and I just didn’t want to write such a sad ending. Second, there are two fabulous and readily available biographies of her—one by David Bodanis and the other by Judith Zinssner—and I thought people already had two great choices of books to read if they wanted to learn about her.

What I came up with was the idea of having the story be about the daughter she left behind. Emile was considered so scandalous and so frightening in her intelligence and accomplishment that she was essentially shoved aside after she died. The women who ran the salons of Paris ridiculed her, probably from envy and a certain viciousness about nonconformity, and men of science tried to minimize the importance of her work.

The scandal of living with Voltaire and then having a baby out of wedlock by yet another man made her a pariah after her death, so I wondered what the life of a little girl born into that situation would have been be like. I imagined a life in which information about her mother is kept from her, while she grows up very much like her in many ways, wondering why she doesn’t fit in and can’t be satisfied with the future others have in mind for her.

Since the reader wasn’t likely to know any more about Emilie than I did, I knew that I had to build in Emilie’s story so that what happens to Lili could be seen in its proper context. All the scenes about Emilie interspersed in the book are based on fact, and my goal was to have Lili’s and Emilie’s stories be on an intersecting trajectory, so that just when Lili is beginning to feel desperate about her own future, she learns what the reader already knows about her mother, and this gives her the insight and strength to shape her own life.

What about the other main characters? Are their answers different to the challenges of the complex French society of the time?

Delphine and Lili grow up like sisters, and the bond is deep although Delphine represents the mindset that could accept things as they are and learn to play the game. She’s no great intellect, although I think she is sweet to the core, and I had so much fun writing her! Julie de Bercy, Delphine’s natural mother and Lili’s surrogate mother, represents a society on the edge of breaking loose from the corseted world of pre-Revolution France and embracing the romanticism and free thinking of Rousseau and others. She also represents another way for women to be a larger part of society. Even if she can’t make a contribution herself, she can run a salon, and she can use her considerable charm to promote a better society that way. Her foil is the rigid and old fashioned Baronne Lomont, who thinks in all sincerity that she is acting in Lili’s best interests by training her to be pious and docile and to accept her role as a wife and mother. I imagine in real life these conflicting ideas were as passionately and aggressively held as they are in my novel.

And of course the other key character is voltaire himself. How true to the facts is your depiction of him?

As an author I feel a great responsibility to the facts, while at the same time I write fiction because I really don’t want to be bound to them. There is a lot of opportunity to be creative in nonfiction, but one has to keep imagination and inventiveness in check, and I discovered in writing my first trade book (the nonfiction Holocaust story (UNTIL OUR LAST BREATH) that those limitations undermined what I consider my strengths as a writer.

At the same time, I think historical novelists would do well to bear in mind that one of the things that appeals to readers about the genre is the chance to learn facts in the enjoyable context of a good story. Lack of faithfulness to the facts, like poor research, will squander the audience’s faith in our books as “smart reads.”

My approach with Voltaire, and with all biographical characters in all my novels, is not to say anything I know to be untrue. Voltaire was, for example, always in trouble with the censors and Emilie did have to go to great lengths to protect or rescue him. Voltaire always had trouble with his teeth and eventually lost them all. He was a flaming hypochondriac and extraordinarily self-centered and self-promoting, sometimes at Emilie’s expense. He lived at Ferney in much the manner I described, and he is revered today for buying the whole town outright and bringing it out of squalor by providing the capital for cottage industries. He and Emilie were lovers until he became convinced his penis was not up to the task, after which they settled into being constant companions and often quarrelsome friends. One of my favorite scenes in the book is when a carriage axle breaks on a winter night and Emilie and Voltaire wait for help to arrive while lying in a cocoon of rugs and furs, looking up at a clear night sky and talking about the stars. That is taken from Voltaire’s manservant’s memoirs just as I present it, embellished only to imagine what they might have done and said.

Is this mix of facts and inventiveness what attracted you to historical fiction?

Absolutely. I am equally a humanities professor and a writer, and this is a wonderful way to be both. I take facts and use my imagination to tell the rest of the story. I think sometimes people get too wrapped up in thinking that only things that can be documented should be treated as true, but how do we tell the truth when the facts aren’t known? If we don’t have any facts about what a famous person ate for breakfast, or where and at what time, is the story of that person better served by making some assumptions or by leaving out breakfast altogether? So yes, I would say I have found the perfect means to teach and create by writing novels.

Lili tries her hand at writing and some of the stories she writes are in the book. Why did you feel this was important to include?

I got about forty pages into writing the book and I realized that the story was rather gloomy and would continue to be that way to a significant degree. Because writing a novel takes such a huge investment of time and effort, novelists keep going by shaping books to what their own temperaments require. I’m an optimistic and happy person, and I want readers to know that they can count on a book from me to be serious and realistic but with characters that sparkle and refuse to be blunted, so that the tone remains upbeat throughout.

The plucky little girl Lili invents, Meadowlark, has adventures that are half fairy tale, half science fiction, and they are written with the voice of the person Lili is at the time, from naïve little girl to intelligent young woman working out her own fears and criticism of her society, much as Swift was doing at roughly the same time with Gulliver’s Travels and Voltaire with Candide. In this way I introduced humor and lightheartedness into the novel at times when the story provided very little opportunity for it.

The key themes in all my fiction are the narrow range of choices for women throughout most of history, but how it is possible, even within these narrow opportunities to make choices. I believe that our choices define who we are as people, and that self-knowledge both drives these choices and is a result of reflection on them afterwards. The key focus in all my fiction is characters who, for the most part, are healthy and strong in mind and spirit. I’ll leave it to others to write books about dysfunctional relationships. I am more interested in how people thrive, and how they build good, abiding relationships with each other.

Finding Emilie: About Emilie Du Châtelet

Emilie du Breteuil’s father was a baron in the court of Louis XIV. As a child, she was given lessons in fencing and gymnastics to help overcome her gawkiness. At 12, she could speak French, German, Latin, and Greek, and as a young woman used her own money to hire tutors to teach her mathematics and physics. After becoming the wife of the tolerant and often-absent Marquis du Chatelet, she took lovers from among the top scientists and writers of the day, At 28, she and the philosopher Voltaire began living openly as lovers at the marquis’ country estate, Cirey. There they amassed a library of 21,000 books and set up labs to conduct experiments in gravity, fire, and optics. Affectionately called “Emilie Newton” by her friends, she wrote many scientific papers, and her translation of Newton’s Principia from Latin to French is still the standard today.

Passionate, vain, materialistic, extravagant, and brilliant, Emilie du Chatelet looked forward to an old age filled with “gambling, study, and greed.” It was not to be. An accidental pregnancy from an affair with a dashing young military officer and poet brought about her death at age 42. Having had premonitions of her death, 6 days after an uncomplicated birth of a daughter Stanislas-Adélaïde, Emilie was back at work. After finishing and signing her last scientific paper that day, she complained of not feeling well, and within hours she was dead. “It is not a mistress I have lost, but half of myself,” Voltaire said upon hearing the news.

Reviews

“Readers, however, may find themselves more intrigued by the scandalous Emilie du Chatelet, a multilingual diamond-adoring card shark as well as a proponent of kinetic energy. In the novel’s prologue, we learn the soon-dead 43-year-old scientist (who it turns out was pregnant from a torrid affair with a younger poet) considered “learning, gambling and greed” the only pleasures left in life for someone of her age. Indeed, a woman ahead of her times.”

Norma Meyer, Sign on San Diego: More gutsy than curtsy Historical novel ‘Finding Emilie’ a good blend of fact and fiction”

“Verdict: Corona’s marvelous scenes of the French Enlightenment in progress will appeal to readers who long for times when anyone of any intellectual claim could dabble in new ideas. Fans of Tracy Chevalier’s Remarkable Creatures will also enjoy.”

Mary Kay Bird-Guilliams, Wichita P.L., KS, The Library Journal

“Finding Emilie is full of insights into the lonely and difficult existence of a woman in that era, especially when the woman is intelligent and unwilling to settle for a normal, shallow existence.”

Bookaholics

“The perfectly blended tale of history and fiction make for an enjoyable read.”

One Book Shy of a Full Shelf

“I loved feeling like I was whisked away to another time, as author Laurel Corona captured the essence of her characters with exquisite detail, making me feel like I had lost a friend when I concluded the novel.”

The Burton review

“Although the work is fiction, Corona achieves her goal of entertaining and educating readers about the lives that women led in 18th Century France.”

Donald H. Harrison, San Diego Jewish World

“…by telling the marquise’s story along with her daughter, Lili’s, Corona brings a changing world, peopled with fascinating historical figures like Diderot and Voltaire, to vibrant life”

Publishers Weekly

“Finding Emilie is a terrific Louis monarchy French historical in which the three femmes are terrific fully developed characters.”

Genre Go Round Reviews

“Readers will relish this deep look at eighteenth century France…”

The Merry Genre Go Round Reviews

“If you enjoy a good historical novel with facts on historical people,historical times and a great story than you will enjoy this one”

My Book Addiction and More

“Corona’s book is a wonderful mix of science, history and romance that shows how the three are connected in more ways than many of us think. Every one of the novel’s characters are charming, particularly Lili. Corona does a wonderful job of portraying the stringency of pre-revolutionary French society and the repercussions that could develop from breaking social rules. Don’t be surprised if you find yourself scowling or laughing out loud while reading, or if you’re enticed to pick up the author’s other books. Enjoy this great read!”

Romance Junkies

“…choosing to read and review Finding Emilie by Laurel Corona was a no-brainer for me…”

Yvonne’s Thoughts

“I really loved Finding Emilie. 18th century France came beautifully alive. Lili was a fascinating character. I loved how she thought for herself and took control of her own life.”

Readin’ and Dreamin’

“This was a very satisfying read combining both the realities and restrictions of the times with the courage and convictions of a smart, strong-willed young woman who is ultimately encouraged and allowed to thrive.”

BookNAround

“The writing is so fluid and draws you into time and place so that you don’t want to leave. The character of Lili is pure fiction but you forget that as you are pulled along in her story. You believe it could have happened. You want it to have happened. Lili is such an engaging young woman that you want to stay in her company.”

Broken Teepee

“Laurel Corona has found a way to bring not only Emilie to life but also to imagine a life for her daughter Lili, who is thought to have died in childhood.”

BookLoons

Ideas for Book Clubs

If your book club adopts one of my novels, I would be delighted to set up a visit. If you are local to the San Diego area, I may be able to come in person, and for others, I am happy to chat by phone.

I’d love to hear your ideas! Write to me, lacauthor@gmail.com, to let me know how your book club meeting went. Send photos and I’ll post them and your event suggestions on the site.

Discussion Guide:

- What does the reader learn about the two great influences on Lili’s life, Baronne Lomont and Julie de Bercy from the letters in the prologue? About the Marquis du Châtelet and his relationship with Emilie?

- In your experience, does childhood personality carry over significantly into adult life, as it does with Lili and Delphine?

- Lili’s Meadowlark stories reflect her fears and dilemmas. What are some of these, and how do they shape what she writes?

- Would you have wanted to be Emilie du Châtelet? What do the episodes from Emilie du Châtelet’s life say about the world of noblewomen in eighteenth-century French society?

- During the course of the book, Delphine seems to be particularly victimized by her social environment, but also masterful at triumphing over it. What in her personality and behavior accounts for this? How does Lili’s temperament make her also a victim and victor?

- Do the politics and science discussed in Julie’s salon and elsewhere in the novel resonate in our world today?

- Were Baronne Lomont and Julie right in keeping so much about Emilie a secret from Lili for such a long time? Would this be handled differently today?

- “The truth is all that matters, all that is really permanent.” Lili comes to an understanding of her mother’s scientific philosophy while wandering through her rooms at Cirey. Do you agree with this point of view? Did Emilie apply it well in real life? Can anyone?

- What do you think of Rousseau’s idea that our upbringing is deliberately intended to deform us to fit the society we live in?

- Are the male characters in the book subject to the deformity Rousseau speaks of? If so, how?

- Emilie du Châtelet says in her “Discourse on Happiness” that it would be better to figure out how to be happy in the situation we face than try to change it, and that the happiest people are those who desire the least change in their lot. Lili misunderstands the meaning of this at first, but comes to see her mother’s view as inspirational and liberating. What did Emilie mean? Is it good advice?

Ideas for Your Book Club Event:

- Get a copy of Candide and find a passage to read to the group (the opening chapter will do perfectly).

- Make up a title for a new Meadowlark story and ask guests to bring ideas for it.

- Rent a corset and panniers and have willing guests try them on. Perhaps a wig in the style of Marie Antoinette as well?