I have always wondered what women were doing in the past, since what’s been passed down is largely the accomplishments of men. Learning that one of the great orchestras of seventeenth and eighteenth century Europe was all-female—and largely foundlings and orphans to boot—was a true thrill for me.

A priest by profession, in his mid-twenties Antonio Vivaldi was renowned in Venice primarily as a superb violinist. In fact, he had barely begun to compose music when he was hired to be the violin teacher for the top soloists at the foundling hospital, cloister, and musical academy known as the Ospedale della Pieta. Vivaldi might never have reached his full potential as a composer if he had not had the coro of the Pieta, a disciplined and skilled ensemble of instrumentalists and vocalists, to work with, and I think it is fair to say that to a significant degree the musicians of the Pieta allowed Vivaldi to become Vivaldi.

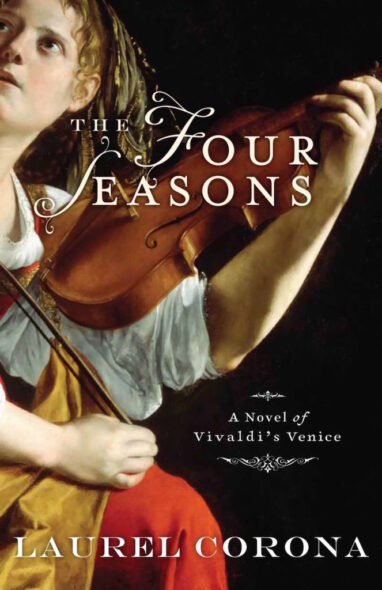

As a professor of Humanities, a woman, and a writer, I found the story of composer Antonio Vivaldi’s involvement with the Pieta endlessly fascinating, and I wrote THE FOUR SEASONS to share it with you.

Synopsis

When a Venetian foundling hospital hires a young priest to give lessons to the violinists in its all-female orchestra, the relationship between the maestro and his cloistered students gives rise to one of the great musical legacies of the Baroque Era.

With music spilling out from a concert in the chapel, three-year-old Maddalena and her baby sister, Chiaretta, are abandoned in the alley outside the Ospedale della Pieta, Venice’s world-famous cloister and musical academy.

High-spirited and rebellious, Chiaretta develops a singing voice that catapults her to early fame, leaving her with the agonizing choice between an aristocratic marriage and life as a musician in the coro of the Pieta.

Maddalena’s path to renown is quieter and more difficult, but when teacher and concert master Antonio Vivaldi notices her deep love for the violin, they begin a musical relationship in which each challenges the other to greater heights.

Despite the limited freedoms allowed to women in eighteenth century Venice, as adults the sisters build rich and meaningful lives of their own, one inside and one outside the confines of the Pieta. Vivaldi’s own career takes him in and out of their lives, bringing complications that are not always welcome but at other times open their imaginations to all that life has to offer.

On the balcony of the Pieta, where the coro performs, the cloister and the outside world intersect. From there, the reader is drawn back into quiet lace workshops, crowded wards, and busy rehearsal rooms; and outward into the dangerous, exotic and colorful world of Baroque Venice.

THE FOUR SEASONS is a tumultous story of women discovering the complexities of their passions and the deep bonds of love, in a setting where music and an extraordinary city become central characters in and of themselves.

TRADE REVIEWS

“Corona’s richly historical novel imagines the lives of two sisters born in eighteenth-century Venice and left on the steps of the Ospedale della Pietà, a foundling hospital and musical academy. Each sister develops a breathtaking musical ability— the younger, more vibrant Chiaretta becomes a beautiful soloist; the elder, quieter Maddalena is a master of the violin. As their lives progress, the sisters find themselves on wildly different paths—Chiaretta marries into a wealthy Venetian family, and Maddalena studies under the brilliant composer and contentious priest Antonio Vivaldi, with whom she develops a forbidden attraction. Yet their strong sisterly bond remains indestructible. Corona covers the full spectrum of Venetian life as she crafts alluring scenes of Chiaretta floating on the gondola at her summer villa with her cavaliere servente, sharply contrasting with Maddalena’s modest quarters and chaste way of life. Complete with a pronunciation guide and glossary, this charming, exquisite, and poetic novel embodies the dazzling light of Venice and the heavenly music of the coro as it portrays two orphaned sisters full of ambition, heart, and steadfast love.”

Annie McCormick, Booklist

“The music students who inspired Vivaldi and the city where they performed the great composer’s works come to life in Corona’s adult fiction debut. In 1695, three-year-old Maddalena and her infant sister, Chiaretta, are abandoned on the doorstep of Venice’s Pietà foundling hospital. Groomed for the Pietà’s renowned music academy, Chiaretta, with her pretty blonde looks and beautiful voice, earns a place as celebrated soloist and marriage to an aristocrat. Dark, quiet Maddalena remains in the shadows until she takes up the violin, and a controversial musician and cleric, Antonio Vivaldi, becomes her teacher. Vivaldi represses his romantic feeling for Maddalena and instead writes concert pieces into which they can both put their hearts. According to Corona, women like the orphaned sisters inspired the fervor and brilliance of Vivaldi’s music. Fans of Tracy Chevalier’s Girl with a Pearl Earring will welcome another novel about how a masterpiece is created. Corona shines when showing musicians at work, especially through secondary characters both real (opera star Anna Giro) and imagined (violin teacher Silvia the Rat).”

Publishers weekly

AUTHOR REVIEWS

“Corona’s ‘THE FOUR SEASONS’ is historical fiction as it is meant to be written– a gripping exploration of the twisting byways of both 18th century Venice and the human heart. Pop Vivaldi’s masterpiece into the CD player, brew a pot of tea, and prepare to relinquish the rest of your afternoon. Corona brings Venice and Vivaldi to life, delivering a stirring story of love, ambition, and music that will keep you reading long after the last note of the concerto has ended.”

Lauren Willig, Author The Temptation of the Night Jasmine; The Orchid Affair

“I’ve never been to Venice, played a violin, or for that matter carried a tune, but after reading THE FOUR SEASONS I feel that I’ve experienced all three, and through them come to a better understanding of the many forms love takes. Brava, Laurel Corona.”

Sally Gunning, Author Bound; The Rebellion of Jane Clarke

“Music and the dangerous, exquisite world of 18th century Venice form the setting of this poetic, sensual story of two orphaned sisters.”

Stephanie Cowell, Author Marrying Mozart, Claude & Camille

“Laurel Corona’s THE FOUR SEASONS is a poignant tale of two sisters layered exquisitely over the exotic world of brilliant priest/composer Vivaldi and his 18th century Venice. The result: a vibrant crescendo of hearts and history…”

Karen Harper, Author The Queen’s Governess, Mistress Shakespeare

“Corona does a magnificent job of showing us the violent contradictions of life in 18th-century Venice, through the eyes of two musically gifted orphan sisters. Their relationships with music and particularly with the complex, enigmatic figure of Antonio Vivaldi are sensitively explored. This novel resists the easy cliché and really succeeds in drawing a world that is both panoramic and intimate.”

Susanne Dunlap, Author The Musician’s Daughter, Anastasia’s Secret

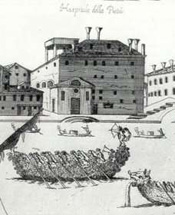

The Ospedale della Pietà

The Ospedale della Pietà was not a convent, or an orphanage, or a music conservatory, or even a home for girls, although it had elements of all four.

It was a lay institution, having no official connection with the church, although life inside its walls was ordered according to the Holy Office, the same regimen of prayers and activities used in convents and monasteries. It was a charitable institution that took in orphans, but poor and indigent parents also abandoned children at its doors, and daughters from wealthy families were sometimes sent to live there, usually for short periods. For only a small percentage of the residents did it resemble a music conservatory, since most girls received only basic lessons.

Contrary to the perception that the Pietà was an all-female institution, a small number of boys abandoned at the Pietà were raised in a separate part of the building. Boys left as soon as they were old enough to become apprentices, but those who were physically or mentally unable to take care of themselves became, like women in similar situations, residents for life.

At times the Pietà had in excess of nine hundred residents, only a few dozen of whom were in the coro. The Pietà was funded in part by the city of Venice and in part by donations, but it required long hours of work by its residents to meet operating expenses. Figlie di comun, as the non-musicians were called, served in various money-making workshops in the Pietà, making lace, mending sails, dying silk, and turning out other desirable products for sale.

The figlie were paid small amounts of money for their work, which were kept in individual bank accounts administered by a board of directors known as the Congregazione. In certain situations residents could buy small things with the money, but it was mostly meant to contribute to their dowry, or to the payment necessary to secure a place in a convent. A small, mostly symbolic portion of their earnings was subtracted as a contribution to their upkeep.

The Congregazione handled fund-raising and banking, set policy, and served as the voice of the institution in civic life. Although music was originally viewed as a skill to increase the marriageability of their wards, at some point the Congregazione realized that the rigid monastic environment provided the discipline, time, and means to develop the exceptional musical talent apparent in some of the girls. The main motivation for doing this was financial, since paying the bills for such a large and expensive institution was always a struggle. Though church services were free, people who wanted to sit down to listen to the coro during the mass and the concert afterwards had to rent a bench. Programs were provided for a small charge. The real source of income, however, came from endowments, bequests, and fees for private concerts coming from wealthy patrons who fell in love with the music, and often with the musicians themselves.

It was, therefore, important to find among hundreds of girls that few dozen who could be trained to play or sing at a professional level. They became figlie di coro, “daughters of the choir.” Since men were not allowed inside the Pietà except under very limited circumstances, the figlie di coro largely taught each other. Each figlia from advanced beginner on up had both a teacher and pupils. The music program was run by several maestre, who conducted rehearsals, oversaw promotions, meted out discipline, and took charge of instruments and sheet music; and sotto-maestre, who were responsible for overseeing lessons and other necessary training for each division of the coro.

The Pietà thrived on self-governance by women, as did the many convents in Venice and elsewhere. Life in the cloister was overseen by the Priora, assisted by others responsible for various aspects of the institution. Women who came to the institution as babies rose through the ranks to become its leaders. In the case of the coro, performing members generally served until they were forty and then were permitted to retire, remaining at the Pietà for the rest of their lives, with few obligations other than occasional duty as chaperones.

The typical resident, however, did not stay for life. Wards of the Pietà, unless they were in the coro or needed as teachers, were often gone before they were out of their teens. The expression “maritar o monacar” (marry or take vows) applied to most young women at the Pietà, just as it described the limited options available to women who lived outside its walls.

Ironically, as The Four Seasons explores, the women of the Pietà and the other Ospedali actually had a wider range of options than women living outside. Here the view of women as capable leaders of communities was encouraged, and women’s capacity to rise to the same level of professionalism as men was demonstrated. Whether she and Maddalena were better off having been abandoned is a question Chiaretta ponders in The Four Seasons, and however unsettling such a question might be today, it provides insight into the shaping influences on the real girls and women who lived in Venice at the time.

(detail on right)

(detail on right)

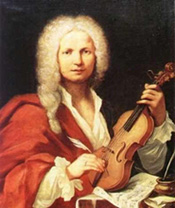

Antonio Vivaldi

March 4 1678 – July 28 1741

Antonio Vivaldi’s life had music in it from birth. His father, a barber, was considered the best violinist in Venice, and played with the orchestra of San Marco. Because the family was poor, Antonio’s best prospects for security lay with the church, and he was ordained at age 26. Known throughout his life as The Red Priest (Il Prete Rosso) because of his bright red hair, after only one year as a parish priest he told his superiors he could no longer officiate at mass due to chronic, severe chest pains (most likely asthma or angina). Hisinfirmity was real and well documented, but it did not stop him from composing, performing and conducting hundreds of his own works, serving as music master at the Ospedale della Pietà, and managing the productions of a Venetian opera house, the Teatro San Angelo, and others in Rome and elsewhere.

by P.L.Ghezzi, Rome (1723)

In 1703 he was appointed violin master at the Ospedale della Pietà, one of four such institutions in Venice with a renowned all-female orchestra and choir. Over the next several decades, he was in and out of residence in various teaching and composing roles, writing hundreds of vocal and instrumental pieces for the Pietà, and sometimes serving as conductor and soloist. On one occasion he was fired, although it appears this was caused by financial troubles at the Pietà, rather than unhappiness with his work or

comportment.

During these decades, Vivaldi struggled to make ends meet by composing music on commission for patrons, as well as writing, directing, and producing dozens of his own operas in Venice and elsewhere in Italy. The circumstances surrounding the composition of Vivaldi’s best known work, The Four Seasons (published in 1726), are unknown. Even the dates of composition of many works that remained unpublished in his lifetime are not known for certain, but some were clearly for the Pietà because they have names of his preferred musicians and singers written on the score next to their parts.

Personal and financial trouble dogged Vivaldi much of his life. Even though he insisted the relationship was platonic, his friendship (and sometimes cohabitation) with Anna Giro, an opera singer, and her sister Paulina raised eyebrows within the church and cost him important commissions. His operatic style lost favor with audiences dazzled by Handel, and his innovations in chamber music were often not fully appreciated.

Nearly penniless, Vivaldi sold off much of his sheet music to finance a trip to Vienna, where he believed commissions from King Charles VI, and perhaps an appointment as court composer, awaited. The king’s untimely death left Vivaldi with no means of support, and he too died soon after. He is buried in Vienna.

The Four Seasons: Q&A with Laurel Corona

How did you come up with the idea for The Four Seasons?

I’m a community college professor of humanities, and one of my textbooks made a reference to Vivaldi’s work with female musicians in Venice. I thought that was interesting and told myself that someday I’d get around to looking into it, probably just to add a little information to my lectures.

Several years later, as I was writing a non-fiction book, I discovered that I really liked the challenge and pace of writing books several hundred pages in length. I knew I wanted to write another book, so I asked myself, “What’s the most interesting subject you can think of right now?” I don’t know why, but the female musicians of the Pieta jumped into my head. And non-fiction never occurred to me. I knew it had to be a novel.

You said the musicians jumped into your head. Why not Vivaldi himself?

Being female, I am always interested in the experiences of women. Vivaldi turned out to be a very intriguing character, and the book is much richer and more complex as a result. I think I might have been able to write a compelling novel even if he were less colorful, but I certainly couldn’t have if the musicians weren’t sufficiently interesting in their own right. And the book would be quite different if I thought of it as being primarily about Vivaldi and his relationship with the women of the Pieta, as opposed to the other way around.

Why did you choose to have sisters as the main characters?

I realized immediately that I was going to have a problem writing about a cloistered setting because the range of experience of the girls and women was pretty narrow. And of course in this case the environment they were being protected from was one of the most dazzling cities imaginable. I knew I had to find a way to bring Venice itself into the story, and the solution I came up with was to have two main characters, one of whom lives as an adult outside the Pieta and one who remains in that rich musical environment her entire life.

I considered developing two unrelated characters of roughly the same age, but I wanted more of a bond between them, so it wouldn’t feel like two stories but a single, intertwined one. I thought it would work better in the later stages of the plot to have them still be connected the way sisters are, even though I know friends can be just as loyal and just as close, and often more so.

There are elements of calculation that go into the early stages of developing a novel that in the end sound horrible. Saying now that there was a point when Maddalena and Chiaretta could have been developed in a significantly different way feels a bit like murder now, because they are who they are. For example, I discovered after I had created the character of Chiaretta that the soprano who sang the role of Abra in Juditha Triumphans was named Silvia. I did a “search and replace” in my text, and I just couldn’t relate to the character anymore, because she wasn’t named Silvia any more than I’m named Gertrude.

The stories are tightly interrelated, but did you end up seeing one sister as the main character, even if just a little?

Not at all. Sometimes one fades into the background for a while, but that’s because writing doesn’t lend itself well to being two places at once. I think both lead interesting lives and have similar levels of complexity, and I feel very deeply connected to both of them.

How did you figure out the plot? How did you know wat was going to happen?

I thought I knew what was going to happen and then it didn’t work out that way. Early on I thought the plot might revolve around discovering something momentous about their parentage, in particular who their father was. As Maddalena and Chiaretta became more full and interesting in themselves, I found I didn’t care enough about who their parents were to put any effort into taking the plot in that direction.

I also thought about having Maddalena leave the Pieta for a while, perhaps to teach music in a convent, because convent life in this era is very interesting to me personally. Sadly, about three-quarters of the noblewomen in Venice were forced to take vows, and of course convent life was significantly affected by the fact that so many of the nuns had not chosen to be there. But eventually I had to admit that my interest in that was forcing the plot in a direction it wasn’t naturally going.

And sometimes minor characters surprised me. For example, when the hooded man reaches under Chiaretta’s dress to touch her thigh, I was as shocked and upset as she was. I honestly did not know he was going to do that beforehand. I went back later and made him a little creepier during the party to make the whole thing work better.

In the end, I just tried to set up complex people in multifaceted and sometimes volatile situations and see what happened. Some authors say their books take on a life of their own and I understand that better now, but for me that’s really only true about what I’m typing right at that moment. The overall story, character requirements, plot trajectories, subplots, backstory, and all those kinds of things take quite a bit of thought, even though sometimes the book spins off in an entirely different direction from what one plans.

What happens after the end of the book?

Sometimes when people ask me that, I want to wave my hands and yell, “They don’t have a future because they don’t exist!” But they’re so real to me, I don’t completely believe that. I suppose the best thing I can say is I don’t know what happened because I lost track of them.

I’m pretty sure Chiaretta will make a spectacular success of her new role as the most powerful woman in Venice, and I bet she remains a fabulous mother. I imagine she may eventually go back to Andrea, but on her own terms. And I can’t imagine what would motivate her to marry again.

Are you a musician?

Only if the kazoo counts!

Do you think this made a difference as you wrote the book?

I have a good background in music history and music appreciation as a result of what I teach, and I think the most that can be said is that a trained musician would have written a different but not necessarily a better fictional treatment of Vivaldi and the musicians of the Pieta.

Music is at the core of the book, and it is extraordinarily difficult to capture in words. I tried to approach it poetically, because that’s the way I hear it. I think there’s actually some advantage to not being an expert, because I was forced to write about the music from my level of understanding, which is probably closer to that of the typical reader.

If, as is often said, all fiction is autobiographical, what does The Four Seasons say about you?

One thing it says is that I am not down on men. I have a male friend who bemoans “sisterhood” types of books, because he feels there is never one decent man in them. I don’t want my books to fall into that kind of thinking just to create the kind of conflict necessary to a good plot. Another thing it says is that I’ve had a great experience having and being a sister.

Does The Four Seasons have a message?

I didn’t go into it with the idea of sending a message to readers, but of course my values and general outlook influence the book. One message is that women are smart and capable, and they (and men too) have the power to shape their lives even in situations that severely limit their options.

Another is that we have to go out and get what we want and say what we need, and that if we don’t know what that is, we can’t expect other people to.

And also the idea that choosing for oneself is an important part of real personhood. To me, The Four Seasons is about empowerment, and I hope readers who can be helped by that message find it everywhere in its pages.