A couple of stories about Canada popped up in my feed today, one from the Rough Guide, saying it was a close second behind Scotland ( where I have also been fortunate to live), as the most beautiful country in the world. It is also, according to US News and World Report, the best country in the world in which to live.

Contrary to the story of American Exceptionalism, and the loud, mind-numbing shows of “patriotism” that flag wavers never seem quite able to put quiet, thoughtful words to, the US isn’t even in the top ten for either. It is a magnificently beautiful country, to be sure, and a great place to be part of the white, employed (with benefits) middle class, especially if you can block out thoughts of how it isn’t so great for others. Maybe it is better as a nation than the last four years have suggested. I hope so, but this era of the president I can’t bring myself to call by name, is like getting in a car accident. Yes, perhaps one is lucky enough to survive relatively unscathed, but the dents are still there.

Yesterday was Canadian Thanksgiving, and it got me to thinking about this country and the ways it has seemed different to me. One thing I’ve noticed is crosswalks, how pedestrians wait for the walk signal even if no cars are coming. Another is how, if a car stops inside the crosswalk for a red light, the driver will back up to make sure pedestrians aren’t inconvenienced by having any of the crosswalk blocked. Another is how drivers stop for pedestrians even before it’s clear they want to cross the street. Checking your phone on a street corner? Expect to look up and see a car stopped, waiting for you. No honking. No frown, despite the little bit of bother you’ve caused.

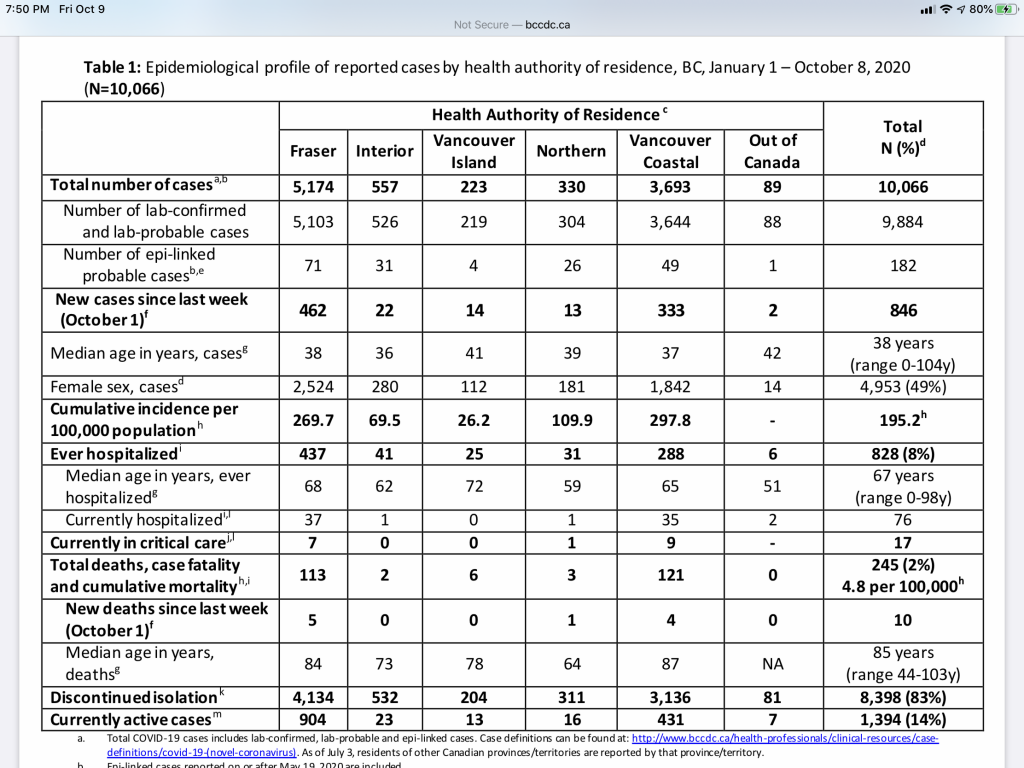

The other day I had the thought that people here wear masks because there isn’t Covid and in the US people wear them because there is. I think in a way, this can serve as the exemplar of so much I have observed here. American unwillingness to come together in the fight against Covid has created a dynamic where people are on the defensive, and even on the attack, against each other. The first week I was out of quarantine I overheard a Sidney shopkeeper chatting with a customer about the fact that there had been a case or two of Covid in two separate restaurants in town. Both venues had voluntarily closed for a few days for more staff training, disinfection, and just to wait out the life of any virus the cleaning might have missed. “Well,” said one, “with a couple of cases, I guess they’ll soon be telling us to wear our masks wherever we go.” The other woman laughed cheerfully. “I suppose so!” No eye rolling, no grumbling. It’s just what you do. And it is why, according to the last news I heard, no one on Vancouver Island is hospitalized with Covid. For more eye-opening statistics, see the table below.

Does this mean Canadians are sheep? Automatons? Not at all. They just get it that they have a responsibility to others. That order breaks down when people make their own decisions about the rules. That certain behavior is required to make life work better for others. That what goes around comes around, and rules create a better society for oneself too. As many of my new friends have put it, being “nice”—and following the rules— is a big part of what makes them Canadian. “How do you get a group of Canadians out of the pool?” a joke goes. Simple. You say, “would everyone please get out of the pool?”

I have been toying with the idea that one difference between the two countries is the national narrative about how the country came to be. I can’t speak to what Canadians absorb as their national mythology, but surely it has to be very different from one in which love of “freedom” is sold as a birthright that must be continually fought for. A War of Independence begins the tale. As the country grew, when societal restraints stood in the way of individualism, a new set of heroes set out for the territories and beyond. And of course, in a tragic irony, the Civil War was at its heart about the freedom to enslave others. The militias and gangs of thugs showing up on the streets and steps of government buildings are the twisted inheritors of an ethos we were taught in school. How else could refusal to wear a mask become elevated in their minds to something akin to heroism in the defense of liberty?

I have been learning how important it is for me to watch for signs—not just the intangible ones, but real ones, in unexpected places. Like the one on a loop trail in Ucluelet saying that because of Covid, everyone must do the trail in one direction to avoid running into people going the other way. I wasn’t tracking the possibility there would even be directions of that sort, and traipsed off the wrong way. Not until after about a mile, when I came to another trailhead and saw the signs there, did I realize my mistake, and that indeed everyone else had been going the other way I felt like a real jerk, and stored away the information that I must be far more observant if I want to fit in here. And yes, I turned around, because I do want that.

the Explorer, but I have to figure I would like her and identify with her spirit of adventure. In first place is one of my childhood heroines, Pippi Longstocking. She was the picture of boundless energy and cheer, making up a fun life as she went along, heedless of what other people thought she should do. She did no harm to anyone, and did so much to enhance the lives of her little friends who before she came along were already dutifully falling into line to become boring, unimaginative adults. I’m not sure I ever wanted to be her, but I certainly did want to know her, to be her friend, to let a little of her rub off on me.

the Explorer, but I have to figure I would like her and identify with her spirit of adventure. In first place is one of my childhood heroines, Pippi Longstocking. She was the picture of boundless energy and cheer, making up a fun life as she went along, heedless of what other people thought she should do. She did no harm to anyone, and did so much to enhance the lives of her little friends who before she came along were already dutifully falling into line to become boring, unimaginative adults. I’m not sure I ever wanted to be her, but I certainly did want to know her, to be her friend, to let a little of her rub off on me.