Okay, I’ve done it. I reopened the manuscript for my new novel, and just as I predicted, I’m back there, ready to dig in, push on, and see what happens next. Two more days of classes before spring break, and then ten days to write.

Diary

Tiptoeing Back

There once was an author Corona

Who said of her new book “I’m gonna…”

Write it, she means,

But then life intervenes

For so long she now says, “I don’t wanna.”

Ahhh, it’s so predictable. The novel languishes while everything else has to take precedence, and now it seems like a territory I’m as reluctant to reinvade as a parent is to go into a room where a child is finally taking a nap.

Will it wake up flushed with sleep, demanding to come out and be part of the fun again? A novel is too inert for that, like the piano keys tucked under a closed lid, or a car waiting silently in the garage. Or like something in the freezer, mutely allowing itself to be pushed to the back, taking on a fur of ice while it burns with neglect….

There I go being a writer again, always looking for the poetic language, the simile, the just-right image. My book is none of those things. It’s too big even to make my long to-do list. I don’t put “go to work” on my to-do list either. Or breathe, eat, sleep, or check my mail. Some things pulse like blood. Some things are on a “never don’t” list we have no need to post.

A book isn’t really like that either. It can be forgotten, at least for a while, but it has this nasty habit of morphing into something really scary, like the monster under the bed that slipped in when you made a quick trip to the bathroom.

I’m afraid of the computer folder the manuscript file is in, like kids are afraid of the house where the crazy neighbor lives. It’s part of a mental map though, and I always know when I’m nearby. In fact, I’m never more than a few mouse clicks away.

A big writing project gets built up in the mind beyond all reason. Writing a novel takes me over, demands more than I think I have to give. But all I have to do is start reading from the beginning and I will fall in love all over again with my story and my characters, and with the sheer joy of being the one who can change it all, or change none of it. Add to that the pleasure of knowing I am finding a way to teach readers important things about far-off times and places. Given all that wonderfulness, t’s hard to remember why I ever stopped writing even for a day.

Just writing this diary entry is helping me get ready for the Fibber McGee closet that is my book. I’ll open the door and it will all come tumbling out on me–every last blessed bit of it, written and yet to be created.

“Welcome back!” it will say.

“I missed you,” I’ll reply.

The Best Unlaid Plans

Unlaid Plans

But Mousie, thou are no thy-lane,

In proving foresight may be vain:

The best laid schemes o’ Mice an’ Men,

Gang aft agley,

An’ lea’e us nought but grief an’ pain,

For promis’d joy!

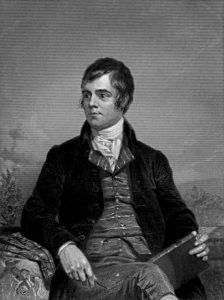

Even without a glossary of Robert Burns’ Scots dialect in his 1785 poem “To a Mouse,” the sentiment is pretty clear: Planning can often be no match for what the world delivers.

I recall one of my favorite New Yorker cartoons of a smiling, briefcase-carrying man in a business suit strutting along thinking about how well he’s taking care of his health, while just above him a safe falling from an upper story is headed straight for him.

When things are going extraordinarily well, it’s natural to project just how good they might get, and therefore it’s equally important to remember that they probably won’t. A few months back I wrote an entry here explaining how when editing and revising is taken into account, a relatively fast writer can still only produce about 2 pages of finished text in a full day. Do the math another way, and it should take only 200 days–less than 7 months–to have a complete 400-page novel polished and ready for publication. I hope that sounds as absurd to non-writing readers as it does to me.

Blue sky, rainy days. Count on them both. The trick, I think, is to enjoy every day even if it isn’t what one anticipated or desired. When I’m traveling and don’t know where I am, I tell myself “I’m not lost. I’m just not where I expected to be.” It’s kind of the same with writing, and I’ve found that what’s true about writing applies to pretty much everything else.

So the report for the last three weeks is as follows: I wrote absolutely nothing, even a diary entry here. I came to a natural break point in the narrative for my novel-in-progress and couldn’t get myself to dive right in to the targeted research for the next section. And then, the deluge!

I can’t agree with Burns that the last three weeks brought me grief and pain where I had envisioned joy, but it did bring one thing after another, mostly good. I spent a weekend reconnecting with twenty of my high school classmates as we celebrated our sixtieth birthdays together (I went to a small high school for girls and we have remained close knit). I was cast in “The Vagina Monologues” at my college and have been rehearsing for that (Come on down to the Saville Theatre at San Diego CIty College on Friday evening March 12 and see me!). A vacation home I have wanted to sell for a long time is in escrow and I am scurrying around to be ready to close. I applied for a sabbatical for the fall semester and am waiting to hear the results. I got PENELOPE’S DAUGHTER back from copyediting, with a quick turnaround deadline I’m working on meeting. And then of course, there’s the less fun stuff, like close to 200 papers and 200 tests to grade over a two-week period, as we reach the first round of midterms in the spring semester at my college.

A novel isn’t the kind of thing where one can say “I’ve got a few minutes–I think I’ll get started on that scene.” To write anything worthwhile requires getting lost in it. Many times I’ve had to break off from my writing to go teach my classes, and I tell myself I’ll think about the novel on the way to school and try to write more in my office hour if no one is there, but I never do. Novels are another world, and if I can’t be there, I might as well do something else as wholeheartedly as I write. Laying plans can be a lot of fun, but knowing how to unlay them with good cheer is the key to enjoying life deluges.

The Right Words

Writing a novel is such a long process that I spend a great deal of time imagining scenes that won’t be written for a long time. This both keeps me going, because I can’t wait to get there, and frustrates me because it’s hard to keep track of all the thoughts I want to remember.

I imagine every author has his or her own way of planning a novel, but I’ve learned from experience not to plan too much. Right now, I am roughly halfway through the first draft of my new novel, and I have a detailed plan only for about the next ten pages, rough notes for the next thirty or so after that, and nothing at all for the rest except a general trajectory for the plot. Even that plan for the next ten was just rough notes a few days ago, but as I near the point that I will begin writing it, the energy of getting down what comes immediately before makes me see the details of what’s next more clearly. By the time I get around to writing the new pages, it will just be a matter of finding the right words.

Sometimes I lie awake in bed in the morning thinking of settings for future scenes, or ponder future dialogue while I walk to my office or work out at the gym. Often these yet-to-be-written parts of the novel come to me with such clarity I can hear the characters speak and know exactly what they will do. I’ve learned from experience, however, not to try to write these scenes down, because so much changes so quickly in a novel that it’s pretty much a guarantee they’ll have to be rewritten anyway to make them fit once I get to that point in the book.

There’s also another nagging problem with writing ahead. Once I’ve written something down, I assume the reader already knows it. I’ll forget that something hasn’t actually happened yet, leaving readers to wonder why I’m casually mentioning something they know nothing about. It’s best, I’ve found, to settle for adding no more than the basic idea for a future scene to my notes, and continue writing where I am at the moment.

Sometimes these future glimpses can be so thoroughly worked out in my mind that I’m even hearing the dialogue, but when I get around to writing the scene, the words will be different than I first imagined them. If a conversation between my characters seems to come out of the ether already well-formed, shouldn’t it remain the way it was, then, now, and forever? It’s weird to get around to writing the scene and find a substantially different way to say the same thing. Or three ways. Or ten ways.

Authors spend so much time revising that we’re all aware that pretty much everything in our books could have been said (or has been said) at least one other way. Somehow, we reach a point where we feel we’ve said it right, but perhaps it’s more accurate to say that we settle for telling a story well enough just one of the possible ways it could be told.

“It’s not good enough, but it’s the best I can do.” If John Steinbeck felt this way, the rest of us are in pretty good company. And if he hadn’t been willing to call that particular book finished, we wouldn’t have THE GRAPES OF WRATH.

Back to work. My new novel isn’t good enough yet, but someday it will the best I can do. You’ll see it then.

What Is He Doing Here?

I’ve written in the past about how I like to sit down at the keyboard and find out what’s going to happen next in my novel. Though some may find this hard to believe, creators of fiction are often surprised by what happens in a narrative they at least theoretically control. Such a surprise happened just this morning to me, and I thought I would share it.

Here’s what I was writing:

The sun passes behind a cloud, echoing the sudden gloom around us. “I don’t think love has much to do with anything,” I say, surprising myself at the thought. I must have sounded wistful, since Elizabeth immediately leaned toward me, still sitting upright on the couch.

“Love?” she says, her mood suddenly bright and mischievous again. “And what do you know about that?”

Diogo standing on the beach, bowing to me as I mount my horse. Diogo’s breath close to my face as I look through the spyglass in the tower. “Nothing!” I say, with what I hope is a casual shrug of my shoulders.

“Nothing?” Elizabeth teases. “I think there’s a ‘nothing’ you haven’t told us about.” She gives Beatriz a conspiratorial look.

“I-.” The barge bumps against the dock and I hear loud voices. Blessedly, we have arrived, and at least for now I won’t have to think of what to say. I look out the window and see carriages and saddled horses waiting, and I make a wild and futile wish that I will be allowed to mount one of the horses and ride off alone, away from Elizabeth’s inquisitive eyes.

Okay, so that’s what I thought was going to happen. The characters are traveling by barge from Lisbon to another royal palace at Tomar, reading a medieval Portuguese romance and daydreaming about knights in shining armor and damsels in distress. Aya is remembering a handsome young man she met the year before. I’m moving right along with them, my fingers flying over the keys.

And then, the unexpected. A character that isn’t supposed to show up until the next section of the book, set a couple of years later, is suddenly standing on the dock! Where did he come from? I don’t have the slightest idea, and I am as surprised as Aya (my narrator) to see him.

I follow behind Elizabeth as she gets off the barge. Prince Pedro is already on the dock, standing with a group of men who have arrived by horseback to wait for us. One man turns around to look where another man is pointing, and my jaw drops.

Diogo Marques. Here. Elizabeth sees my expression and her eyes go back and forth between Diogo and me. My cheeks are so hot they must be red as coals. She knows.

I look up and see Diogo staring at me. It takes him a minute to recognize that the stylishly dressed girl with the princesses is the same one who tore around Sagres with hair as wild as her horse’s mane, her hands and feet caked with beach sand.

And then he looks away. I’m not sure what I expected, but after months of acting out fantasies about knights and maidens, I suppose a little part of me thought he should fly to my side and cover my hand with kisses. I’m hurt at his response, and wonder which of the two things, Diogo’s indifference or Elizabeth’s crazy ideas about love, will be harder to handle at Tomar.

Suddenly everything changes. The scenes at the royal palace at Tomar will be very different from what I had imagined because the young man Aya has a crush on will be there–and Elizabeth is just not the type to leave it alone. The plot opens up, although I’m not sure just how yet.

There’s so much more I can do with the next ten pages than I had thought. My characters are conspiring to make my novel better than I know how to do all by myself. So Diogo, Aya, Elizabeth, I can’t wait for you to tell me what happens next! It’s too bad I won’t find out until tomorrow.

Another Day, Another Two Pages

I’m often asked how much I write in a day, and the answer is that there is no good answer. Usually, it’s only early in the process that the word count “counts.” The hours spent revising and editing–which often add up to far more than the hours spent drafting–contribute little to the total number of pages. How much can I rewrite in a day? How much can I edit in a day? I don’t know the answer to that either.

In an excellent session, when I have a full day to work, and when I know where everything is going and I just have to get it down, I can draft about 8-10 pages (2400-3000 words). The next time, I go back over it and spend quite a bit of time making it better before moving on to draft more. For a while, these “pages in progress” will become a starting point for my read-through before I get down to new writing, so they will continue to be tweaked and polished, by now mostly for the smoothness of the read. Then, as a new section of text becomes my focus, these pages will recede in importance, not to be worked on again for quite a while.

I have a full-time job as a professor of humanities at San Diego City College, so I don’t have many full days to devote to writing during the semester. Adding in early mornings and weekends, it probably adds up to a two-thirds job during the school year and a job and a half on breaks (I’m pretty compulsive about a work in progress). Let’s call it pretty close to a second full-time job over the course of the year. SInce it takes me about a year to get a first draft completed and revised well enough to give to my agent to market, let’s call that 50 roughly 40-hour weeks, or 2000 hours. Let’s say for sake of easy math that the manuscript is 130,000 words (typical for my books). That’s 650 polished words, a little over 2 pages a day.

I don’t sit down and come up with 2 polished pages of text and move on the next day to do 2 more, so I can’t say if 625 words a day sounds about right. But perhaps it will be instructive for novice writers to see how little a full, tough, exhausting day’s work adds up to. And, I might add, I work faster than most authors I know.

Writing at a publishable level is a long, long, process. I imagine if authors were asked for one single image of themselves at work, they would describe themselves mired somewhere in the middle, because that’s where we spend most of our time. Even prolific authors don’t start a book too many times in life, and most finish fewer than they start. It’s successfully dealing with the endless middle that matters most.

Channeling Aya

There’s a magical point in writing a novel when I start seeing the whole story laid out in front of me, when I think I know how one thing leads to another, how the pieces fit. The conceptual outlines I make for chapters start being what really happens in those chapters rather than wild stabs at where the story might be going. I start to hear the voice of my narrator whispering in my ear, telling me how relieved she is that I have finally begun to get her story right. I start to know instinctively how she will react in a given situation, to understand her sense of humor as well as her soft, vulnerable underbelly, and her most secret desires.

It’s a huge turning point in a novel because I know from that point forward my role will change from inventor to discoverer. It’s difficult to explain this to non-writers, but every novelist will understand what I mean. Of course we still write every word of our books, but the words seem to come from someplace else, as if there really are people out in the ether who have somehow managed to get into our heads and are telling us what really happened to them so many years ago. Forgotten for centuries, they are speaking again through us. We are not making it up. We are recording what we are learning from them, being pointed in directions the story must go to be true.

Before I became a novelist I used to roll my eyes when writers would talk as I am talking now. “Oh, right,” I would think. “They’re just channeling ghosts, just writing it all down. Sure.” I didn’t see how it was possible that writers could get to the point where they lose the feeling that they are creating something strictly from their own imagination, making it all up as they go along. But it does happen.

I’m pragmatic by temperament, impatient with supernatural explanations of things, but I do sometimes think that I have tapped into stories of people who really existed, stories that have been overlooked, forgotten. Maybe I’m putting my own shape to the details or getting some of them wrong, but I believe that the lives I write about were actually lived by someone, sometime, somewhere. I want to get it right because they want to be heard.

And once they know they have me hooked they are merciless, disturbing my sleep, distracting my days. “Come on,” they say, “I’ve been waiting a long time for you to hear me whispering to you.” Hold on a minute, Aya ( she’s my new heroine)–I’m typing as fast as I can!

Notes from the Driveway

The vast majority of accidents happen within a few miles of home. This was an argument often heard while a nation was slowly changing its culture to include the automatic fastening of seat belts upon getting in a car.

My father understood this long before Detroit did, buying packaged seat belts and installing them himself on our family car as far back as our 50s-era Ford station wagon. Back then they were called safety belts, and “fasten your safety belt” was the travel mantra of my family. We were routinely buckled up in belts that look like the airline seat restraints of today even before we left our driveway in what was then the very sleepy town of Danville, California. East of San Francisco, the entire area is today covered with upscale houses, one of which is the home of Captain Sullenberger of the “Miracle on the Hudson.”

But I digress. When that ad campaign first came out, it seemed to imply that the drive between home and grocery store was for some reason more laden with potential to kill and maim than hurtling down a freeway, or driving the switchbacks of a gravel cliff road in the Andes. This purported menace doesn’t make any sense until we realize that on every trip we take, whatever its length, we pass through our own neighborhood twice, once going and once coming back. We’re within a few miles of home more often than we’re anyplace else in our car, so of course the odds favor that will be where an accident will occur.

So what does this have to do with writing? I’ve reached the end of the first section of my new novel–roughly the 100 page mark. I can’t really call this the first draft because I’ve been working and reworking the material since day one, and I still need to go back through it a few more times now that I know my characters, plot, and settings better.

Once I’ve polished, tweaked, added, subtracted, and refined in numerous big and small ways, I’ll send the manuscript off to some carefully chosen first readers and while I am waiting for feedback, I’ll start doing some focused research and planning for part two. A few months from now, when I am at the end of part two, I’ll revise parts one and two again. This circling back through the manuscript will happen until the book is complete. Because writing a book is an additive process, this means that the first ten pages will get revised countless times because they’ve been around the longest, page eleven to fifty will be looked at almost as often, the first hundred quite a bit, and so on.

But what about page four hundred? By that point everything is usually really humming. There’s less to go back and fill in or change, since I already know the world of the book so well. But even if that weren’t the case, it would be unlikely the final pages would ever receive the kind of repeated attention the beginning got.

It’s funny how rarely this reduced attention is apparent in published books, but I wonder whether perhaps those books that disappoint, the ones that seem to lose steam and/or focus toward the end, are impacted by the pattern I describe.

The first section of a book is like the patch of road closest to home, the one traveled again and again. When we reach an entirely new destination three to four hundred miles–or pages–later, we don’t experience every curve, every bump in the road so thoroughly. But then we don’t need to, since every mile, every page, adds to our experience, our ability to navigate well through whatever lies ahead. We manage to get to the end one way or another even if we’re dog tired and the road is not a familiar one.

And don’t forget–most accidents really do happen close to home. Fasten your safety belt, everyone!

Check Out My Updated Photo Gallery!

As I mentioned a little while back, I’ve been working with Blue Jay Tech to upgrade my photo gallery. It’s now live! Go to the lower left of the home page and click “view the image gallery.” Let me know what you think (lacauthor@gmail.com). It’s still a work in progress, and I’d love feedback.

Did It Make You Cry?

On New Year’s Eve, I watched the New York Met’s Gala on television. (Okay, I was recovering from surgery–what’s your excuse for being home on party night?) The big appeal to me was that Thomas Hampson–one of the best operatic baritones of our time–was the guest artist, and I am a big fan of his work. At the intermission there was a pretaped interview with Hampson at his New York apartment, and the conversation came around to something so relevant to the writer’s craft that it took my breath away.

On New Year’s Eve, I watched the New York Met’s Gala on television. (Okay, I was recovering from surgery–what’s your excuse for being home on party night?) The big appeal to me was that Thomas Hampson–one of the best operatic baritones of our time–was the guest artist, and I am a big fan of his work. At the intermission there was a pretaped interview with Hampson at his New York apartment, and the conversation came around to something so relevant to the writer’s craft that it took my breath away.

He was asked whether he ever gets carried away with the emotions of the arias he sings, wanting to cry, for example, if his character is sorrowful. I don’t recall his exact response, but here it is in summary. “Look, maybe people watching this won’t understand, but no, I don’t. I am there to put over the emotion to the audience but I can’t get involved in it myself if I’m going to do that. If the soprano in the role of Tosca broke down singing ‘Vissi d’arte,’ the audience would know they had seen something unusual, something noteworthy, and they might even feel they had been privileged to witness it, but it would have totally violated, completely ruined what Puccini had in mind for that piece of music.”

In other words, if Puccini wanted snuffles and boo-hoo-hoos he would have written them in (it does happen in opera occasionally). If there are to be any tears, they should be limited to the audience, not the performer.

When Hampson made this point I was reminded of the times when readers ask me if I cried while I wrote certain scenes in my books. My answer pretty much restates what Hampson said. Writing, like singing, is a job. It is my job to produce an emotional reaction in others, and to do that I have to be operating on another wave length entirely. Imagine a scene where a character is finding out, for example, that her best friend is having an affair with her husband. The writer has to imagine how the character would feel. He or she can’t write the scene as “I just can’t believe how terrible this is–I feel so bad for her–she’s [blubber, blubber], she’s–sssuch a good person. I really hate her friend!!!!!! Oooh, I’d like to wring her neck!” The writer has to stay out of it–a weird thing to say since the writer is inventing it–but true. “How can I get the reader to empathize?” “How can I set the scene to give the maximum emotional effect? What might the character be holding, doing, seeing?” These are writerly questions, and they take a clear, not a tearful eye.

So no, I don’t cry when I write. I do admit that sometimes when I reread a scene, after it’s published and it’s too late to edit, I may tear up a little. “Wow, that’s really sad!” I might say to myself. But that doesn’t happen very often, and when it does it’s because I’m not thinking like the writer any more. My guess is that Hampson doesn’t cry when he listens to a CD of himself either. He. like artists in any field are probably far too busy being oddly detached, picking it apart. What did I do there and why? What might I have done differently, done better? And then of course there are many “ouch” moments–the points where you wish you hadn’t done something that way at all.

Cry? That’s for other people’s books.