It’s easy for non-writers to understand how writing can be an emotional experience, but most people who went to college probably remember research papers as dry-eyed experiences–especially if they involved all-nighters!

I can’t imagine any historical novelist sticking with a topic that didn’t leave him or her speechless from time to time, needing to step away and let the magnitude of some events seep into a mind reluctant to believe. I have had many such moments, beginning with my first trade book, Until Our Last Breath, a nonfiction work on Jewish resistance during the Holocaust, through my sixth, the just-completed novel The Intuitive.

The latter provides the freshest moments of emotionally wrenching research, and I want to share one of those with you now and the second in a subsequent post.

Ever since reading the late Stephen Jay Gould’s magnificent 1981 work, The Mismeasure of Man many years ago, I’ve known about the history of intelligence testing, and the blatant racism, sexism, and classism that went into early efforts to stratify people by intelligence (and therefore worth). American scientists were major participants in this, as a means of justifying slavery, and later to support anti-immigration sentiments. In the early twentieth century, an American psychologist, H.H. Goddard, known as the father of modern eugenics, received permission to conduct research at Ellis Island, whereby women he considered gifted with special powers of intuition would scan incoming immigrants and identify on sight those they believed were feebleminded. Few could pass tests that were so out of the realm of their life experience, and those who could not were deported.

I read Gould’s book long before I had any idea I would become a novelist, but I was so moved by the vision of the “intuitives” at Ellis Island that years later the story of these women and their impact on other people’s lives jumped to mind as something important to tell. The topic had to stand in line, however, and finally in 2011 I got around to it.

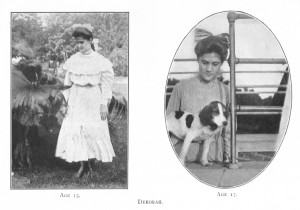

But the teary-eyed part of the research didn’t come from reviewing Gould. It came when I was digging further into Goddard’s most famous work, a 1912 study of a young woman, “Deborah,” from a family living in the Pine Barrens of New Jersey whom he called the Kallikaks. She was the central case study in his theory that “feeblemindedness” was inherited from shiftless, criminal ancestors, and the only way to avoid moral and intellectual degeneration in America was to build colonies where the current generation could live away from “good” society and, most important, be kept from breeding.

“Deborah” came to the Vineland School for Feebleminded Boys and Girls when she was eight. She was never permitted to leave because it was believed that “morons” (a term Goddard coined) had no moral sense and would fall into criminality if left on their own. She was treated as retarded her entire life, though the many abilities she showed, including excellent skills as a tailor, were commented favorably upon and she became a kind of unpaid assistant to the staff.

What took my breath away was the conclusion of contemporary psychologists looking at “Deborah’s” file. They believe she was not retarded at all, but had a learning disability affecting her performance on the kinds of tests they were using to judge her. The file is full of laudatory references to her many capabilities, but nowhere does anyone appear to have questioned whether she should have had her freedom taken away. Though life on the outside was not that pleasant for any working woman, still there’s something about that story that sucks all the oxygen out of the room.

And of course Deborah was not alone. All over the country, men were institutionalized for being gay, and women for being “hysterics, which often meant no more than being defiant. All over the country one could go to jail for loving a person of another race. All over the country, Jews and people of color found doors slammed in their faces. “Life is so nice the way it is,” was the cry of the comfortable. “Why do all of you want to spoil everything for us?”

The Intuitive has a fictional protagonist, wealthy socialite Zorah Baldwin, who serves as one of Goddard’s “intuitives” at Ellis Island. Through her work there and a budding friendship with “Deborah” that begins during a visit to the Vineland School, Zorah breaks out from the narrow world she grew up in, to explore the realities of the Lower East Side and the exploding social issues of the time, including Women’s Suffrage which I will discuss in my next post.

And of course, for her to do that, I had to explore these realities first, taking a lot of breaks to catch my breath, as I staggered my way through some history I think most of us would prefer not to know too much about. But since my self-appointed job as a historical novelist is to bring to light forgotten women, I present a bit of the good, the bad, and yes, the ugly in my new work. The Intuitive is with my agent now, and I will keep you posted here and more frequently on my “Laurel Corona, Author” page on Facebook.