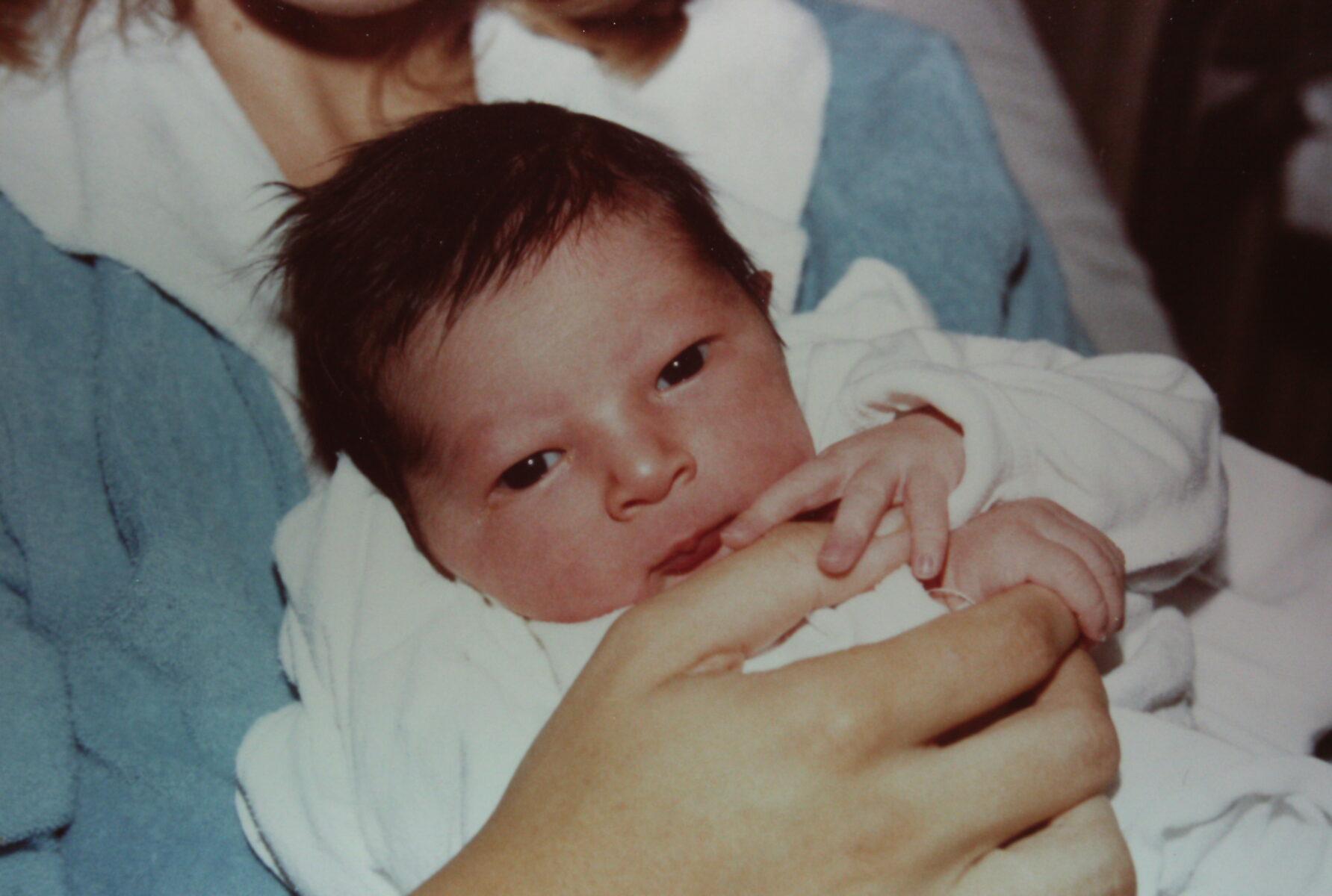

Ivan died nine months ago. Today is his birthday, so the time after Ivan has now been the same length as the time before he was born. In between were forty-three years. This photo was taken forty-one years ago today, when his more birthday-experienced big brother Adriano was showing him how to blow out the two candles on his cake.

I recently read something to the effect that the body often moves forward too quickly in the aftermath of a great loss. There is, after all, so much that needs to be done. But in this burst of activity to deal with the work a death brings with it and to try to reassert normality, the spirit may get left behind. That is what the last nine months have been like for me. I was on my way to Singapore when I got the awful news, and spent the next month and a half doing my job as a cruise lecturer. I came home and had only a short break before I was gone again to the Canaries and Western Mediterranean in mid-March until early May. A stay for a month in the Comox Valley to explore the north of Vancouver Island filled up the rest of May, and I was gone again to the British Isles and Iceland in mid-June until the beginning of August.

Since I got home, I have been busy getting ready for my next assignment and editing a book. Despite the work load, my life has been normal and steady enough in the past eight weeks to get back into my routine and take a few deep breaths. It is only in doing so that I have become aware of how much I have let my soul lag behind. ‘I’m fine,” I have said to everyone who asked, but I guess I hadn’t stopped to turn around and acknowledge my spirit calling me to wait for it.

These last few weeks, one health warning after another has slowed me down, and my soul has been catching up. I am acknowledging that all this busy-ness has been a way to avoid the pain that reintegrating my soul would cause. I have always been intimidated by my own strong emotions, trying to make them smaller, less loud, less insistent, less relevant. This hasn’t worked well, I admit, and has caused some big problems for me in the past, but it’s a pretty entrenched habit by now. I am beginning to understand the imperative to be more honest with myself because I can’t have a healthy rest of my life if I don’t do a better job of knowing my own heart.

In a blessed confluence of events, the High Holy Days coincided not only with a health reckoning but also with Ivan’s impending birthday. Central to the period of confession, repentance and atonement is a moral reckoning with one’s shortcomings. For almost the entire period of the Jewish new year, I dealt with other complex relationships in my life, saying “it’s too soon to think about Ivan this way. I’ll do that next year.” Except my soul didn’t let me.

The night before Kol Nidre, the beginning of Yom Kippur, I had a dream I haven’t had since my teaching days. I am supposed to be giving a final exam, but I am far away, unable to get there on time. I haven’t prepared the exam and I desperately need a shower and shampoo before, very late and with nothing in hand, I have to face my students My friend Annie, also Jewish, jumped on this dream when I shared it with her. ‘You are not prepared for Yom Kippur. You have left important work undone. You are not cleansed yet.” Bam! Every key element of the dream accounted for.

No wonder I woke up feeling sick the next morning and was not able to go to Kol Nidre that evening. I attended on Zoom, which enabled me in complete privacy to focus on both Ivan and Adriano. I didn’t need to hold back big noisy tears. I could talk out loud. I could pace. I ended up sitting down and writing them a letter in which I spelled out all the ways I felt I had missed the mark with them, all the ways I had betrayed the trust they put in me to be the solid foundation on which to build healthy adult lives. (Don’t argue about being too hard on myself, if that’s what you’re thinking. I needed to be brutal in order to move beyond this.)

Then the most amazing thing happened. I felt a softening towards myself, a realization that I had also been a wonderful mother. I wasn’t perfect and I would like some big do-overs, but given some pretty dire circumstances, I had done the best I could. Words of kindness flowed onto the computer screen as if my children were writing them.

I am forgiven. That doesn’t mean I am done with the reckoning. It doesn’t mean I can stop trying to understand why I wasn’t stronger, or figuring out how to take confession the rest of the way to atonement. I can’t change the past, so I atone by how I handle the future. After Adriano died, I tried to see his face in any troubled student who stood at my office door. I asked myself, “What do I hope a person in my position would do if it were Adriano standing there?” Then I did it. I can hold that idea front and center again, falling short over and over, but continuing to try.

As I walked yesterday evening along the sea cliffs near my home, I felt Adriano and Ivan fall in step with me, lacing their elbows with mine, one on each side. I felt for a moment as if I were being lifted and carried along, and indeed I was.

‘We’re fine,” I felt Ivan say.

We.

He’s found his brother and he is fine too, although Adriano is quieter. I think there is some more forgiveness to work on there, but I am not afraid to do that now. I want to do it. I asked them to stay close because I need them beside me to use my remaining time on earth as fully as possible. I can’t do that without revisiting the mess my life was at the time Adriano needed me most, but I know they will be there when I call out for them, to temper my self-criticism with their love.

I looked out over the driftwood-strewn beach at waves splashing white onto dark rocks. The ocean glimmered silver in the moody afternoon light, and I was filled with gratitude that life has offered me so much joy along with the sorrow. I want to revel in this world as long as I can, but when my time comes I will leave it behind with love and gratitude and go with happy heart to be with my boys wherever they are.