Tomorrow is my last full day in quarantine. It is also my mother’s 101st birthday. She didn’t live to see it, dying in 1986, three years younger than I am today.

My mother, Jean, is the reason I am here in Canada. She was the firstborn child of my English grandmother and her husband, my grandfather, an American chemist working for Miner Rubber Company in Granby, Quebec.

Jean and her younger sister Catherine, or Kitchie, as she was always known, spent their early childhood in 1920s Granby, where traveling in winter was done by sleigh, rivers were crossed by boat, and any further travel was done by train. No cars. They rode their ponies to go get the mail in town. They went to a small school where many of their classmates were First Nations children.

Jean is in back row, next to taller student standing to the right of the teacher. Her sister Kitchie is in front row, third from left.

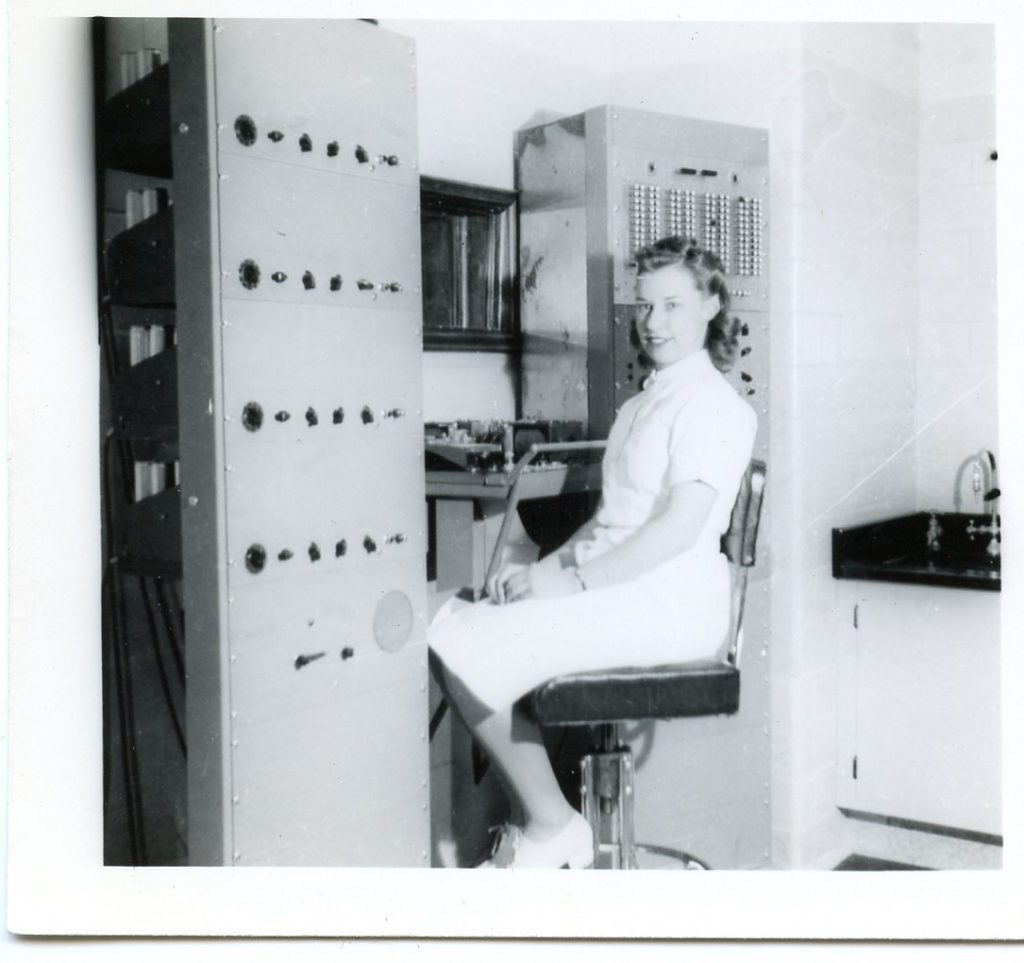

When Jean was seven or eight, the family left Canada for Wausau, Wisconsin, where she graduated at the top of her high school class and went on to the University of Wisconsin to study Chemistry. She ended up completing a Master’s degree in Chemistry, quite an accomplishment for a woman of her era. She got a job at the Mayo Clinic working in the new field of electroencephalograms.

My mother at work in the Mayo Clinic

In college she met my father, Ivan Weeks, and they eventually married. By the time I was born they were living with my two-year-old sister in Altadena, California, in the San Fernando Valley, where there were more orange and walnut trees than houses in an area that is now packed with suburbs and “Val Gals.”

Shortly after I was born she was diagnosed with ankyloid spondylitis, an inflammatory disease that, over time, can cause vertebrae to fuse. It is possible that her pregnancies may have triggered the disease, a fact I only learned recently and I don’t know if she ever knew. This fusing made her spine less flexible and she slowly froze in place from her waist to her skull, with her head and neck slightly askew. Her ribs were affected as well, making it necessary for her to breathe using muscles of her diaphragm because her ribs could not expand properly. This was aggravated in her case by asthma, which my aunt recalled began after a bout of whooping cough as a child.

Once she became a mother, and once she began dealing with the permanent double disability of the spinal fusion and impaired breathing, that was the end of any hope for a career. Actually, even if she were in robust health, that just wasn’t in the cards for women with professional husbands and young families in that era. I have written about this aspect of my mother before, and I encourage you to read my 2019 blog post, “Anniversaries,” here to learn more about growing up with this remarkable woman.

What amazes me most about my mother is that I never for a moment saw her as disabled. I don’t think she saw herself that way either. There wasn’t much she couldn’t or didn’t do, although often in her own way. She drove, but with the addition of big mirrors that stuck out from both sides of our car because she couldn’t look over her shoulder to see what was behind her. One thing she couldn’t do was ski. While we were on the slopes, she sat in the lodge and read and knit all day because she couldn’t turn to catch a chair lift or see what was coming down the hill. She was the best Girl Scout leader in town, and I was always jealous because it was for my sister’s troop and I hated mine. She became skilled at many crafts, including mosaic and wood carving, and we feasted on vegetables and berries from her garden and fruit from our small orchard in season, and on jams and canned fruit she made herself.

My mother did not become an American citizen until she was around forty, I remember going to San Francisco for her to sign the naturalization papers, mostly because we went for sukiyaki on Fisherman’s Wharf afterwards, a family treat. Apparently her main rationale for this change was that she had gotten tired of not being able to vote.

As she grew older her lung capacity decreased, and in her last years, it was at about 20 percent. Catching a cold was potentially fatal because any congestion would make getting enough oxygen impossible. Still, she went out and about with a breathing contraption in her car, and I rarely heard her turn down a chance to go do something fun because it would be too strenuous. We camped with my little boys, and visited the wonderful Native American sites around Los Alamos, where she moved with my father in the 1970s. A doctor once told me he was astonished that someone with her lung condition wasn’t in a wheelchair. My mother never even used a walker.

With my son Ivan channeling the Lone Ranger in Los Alamos, New Mexico

She celebrated her 67th birthday with her sister, my Aunt Kitchie, on August 20, 1986, and apparently was not feeling well. She had to take her temperature several times every day, because any rise could signal the onset of a cold, and she needed to get to a hospital immediately to save her life. Kitchie found her the following morning dead at the breathing machine she kept in her bedroom. She must have felt short of breath and gotten up to use it. She took her temperature too—it was noted in her log. One degree above what it had been that morning.

My mother died thirty-four years ago this Friday, the same day I leave quarantine. On that day, I will receive from her a final precious gift, the chance to start my new life in Canada as a citizen by descent. I think she would be astonished and pleased that the little girl grinning in the school photo was already carrying that gift for me.