How lucky could a writer be to have a partner whose idea of a good summer read is the fiftieth anniversary edition of Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style?

Just this morning he read to me from the foreword by Roger Angell, E.B. White’s stepson. Angell describes White typing his weekly New Yorker column as sounding like “hesitant bursts, with long silences in between.” I can’t imagine a better description of what it is like to write, or a better statement than the one White frequently made about the result: “I wish it were better.”

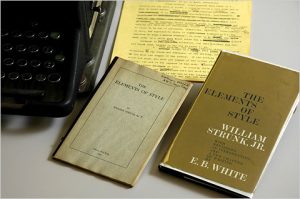

Actually “Strunk and White,” all the identification this slim volume needs, has its origins ninety years ago, when E.B. White took a course from Professor Will Strunk at Cornell University. One of the required texts was a roughly fifty page, self-published text by Strunk, presumably designed to help students write papers that would not be quite so painful to read. Almost forty years later, in 1957, White dusted off this little treasure, and with minimal updating, launched it into the realm of the true classics.

The fiftieth anniversary edition contains all Strunk’s original, pithy advice, plus an essay by White, who is perhaps best known as the author of Charlotte’s Web. “The preceding chapters contain instructions drawn from established English usage,” White explains. “This one contains advice drawn from a writer’s experience with writing,” and is meant as “mere gentle reminders [of] what most of us know and at times forget.”

So here, dear readers (and writers), are a few of my favorites:

“Write with nouns and verbs, not with adjectives and adverbs. The adjective hasn’t been built that can pull a weak or inaccurate noun out of a tight place.” So true! It is with these that we build a strong text, relying on modifiers only when the situation cries out for more than powerful, well chosen nouns and verbs can provide.

“Do not dress up words by putting ‘-ly’ on them, as though putting a hat on a horse.” I’ve made a point in my recent work of trying to avoid all use of “-ly,” unless to do so creates worse difficulties in producing crisp, succinct writing. This always has to be the ultimate goal, but it’s better to show what a sly smile looks like, than say “she smiled slyly.”

And my favorite, though most painful of them all: Revise and rewrite. Remember it is no sign of weakness or defeat that your manuscript ends up in need of major surgery. This is a common occurence in all writing, and among the best writers.” I’m in good company, apparently, because I think I spent more time revising Until Our Last Breath than I did writing the original manuscript. It’s no fun, and as I near the end of the first draft of my new novel, The Laws of Motion, I know much of the heavy lifting still lies ahead. Everyone who’s ever written a book, or even a page, knows to expect to mess with it over and over again, and perhaps to end up throwing it away altogether.

Our first drafts are the pass in which all the potential of the material cries out and it’s our job to impose discipline on it. Sometimes we don’t want to do that, and I think we shouldn’t worry about it too early in the process. Often it’s easier for others to assess a new work as a whole, and the person we become by writing it (yes we do grow and change!) frequently delivers some good messages about how it could be improved.

In the end, the taskmaster for all writers is the same one E.B. White listened to, the one that says “make it better.” And every writer knows that such a taskmaster is never silenced just because a work has an ISBN number and a cover around it. I wonder whether Strunk or White ever winced at their own published writing. I know I sometimes do at mine.

HAPPY 50th BIRTHDAY, STRUNK AND WHITE!