No question about it—travel is stressful. Since several people I have traveled with have commented about how I never seem to get freaked out by anything, I guess I might have some worthwhile thoughts to share.

Corona Axiom 1: There is a difference between travel stress and travel anxiety.

The body doesn’t like long haul flights, even if you are lucky enough to upgrade to business or first class. The body doesn’t like to deal with heavy luggage. The mind doesn’t particularly like dealing with the unfamiliar, especially when jet lagged. There’s the aching head and muscles, the incomprehension of looking at money one has never seen before, of dealing with the facts on the ground rather than the way things looked on a map or in a guidebook, the realization that the person you really need to help you has no idea what you just said. Some things about travel are just never going to be easy.

But travel anxiety is different. Worrying can be far more exhausting than any difficulty or discomfort we actually face. And though anxiousness has some of its roots in basic personality, there’s a lot about travel worries we can manage and minimize.

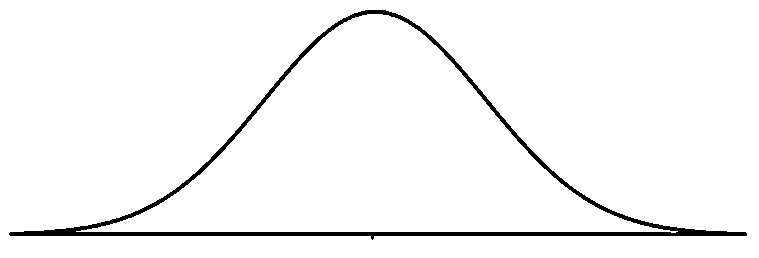

I once came across a diagram showing how we perceive stress.

Here on the horizontal axis we have perceived difficulty of the task, ranging from “piece of cake” on the left to “no way in hell”on the right. On the vertical axis the bell curve measures the stress we feel. The interesting thing is that on the “no way” end (on the right here), we feel about the same lack of stress as we do for easy tasks. To illustrate, if someone asked me to turn on the lights, I know I can do that, so no stress. If someone asked me to do a triple back flip on the way to the light switch, I don’t feel stressed because I know I can’t do it. When the answer is a sure thing, whether yes or no, the situation is simple.

The point the author of the model was making is that stress builds as we wonder whether we can actually do what is being asked, with the most stressful point being the 50/50 chance situation—when you just don’t know if you can get through security before you miss your flight, or you just don’t know if something you need really is lost, stolen, or forgotten, or just hiding somewhere in the recesses of your travel bag.

There’s one more important element to this bell curve, and that is that the outcome has to matter. If you can’t find your passport or glasses, or prescription meds, the stress obviously will be more than if you can’t find that furtive granola bar. If all you want is a quick hop from Los Angeles to Las Vegas, or Philadelphia to New York, missing the plane probably will delay you an hour or two. Unless you have theatre tickets to Hamilton that night, or it is the holiday season and getting another flight might be hard, or you are rushing to get to a dying loved one, or you spent your last dime on a non-refundable and non-transferable ticket, there’s just not that much at stake.

But that peak anxiety at the top of that bell curve—when we don’t know if we can actually do something and it really, really matters that we do—is something we can train ourselves to avoid, at least to a degree.

Sometimes the answer is to dial down how important it is to have the situation be just the way you want. There are other ways for things to work out. If you are lost, you can try to see it not as a disaster but an opportunity to do, see, learn something different. You aren’t lost, you’re just not where you thought you would be. If it rains the one day you are in a new and exciting place, don’t fret, just get wet. You’ll get dry again. Happens every time.

The second is to improve the odds that what you want to happen actually will. You can allow way more time than you think you need to get to the airport. You can buy travel insurance to make Plan B less financially stressful. You can get every last detail in place the night before—all these ideas being so obvious they hardly need saying. Making lists can help. So can physically blocking the front door with things you can’t pack until just before you leave.

In my case, for example, flights to Bhutan on the tour I arranged for April only go twice a week at 6am. If I miss my flight, I am not going to Bhutan, because I don’t have enough time between cruises to wait for the next flight. Therefore, the chances of feeling stressed about missing the plane are pretty high. So the night before, I am going to fork out the extra money to stay at the hotel right in the Singapore airport, set the alarm on every device I have, plus arrange a hotel wake up call. I probably won’t need any of it because I won’t be able to sleep—I never sleep well when I have something important riding on the effective functioning of an alarm. But so what if I don’t sleep? I’m going to Bhutan!

When I have to catch a ship for an assignment, I assume things could go wrong—lost luggage, missed connections—so I go a day, or even sometimes two days early, depending on how dire the situation could become. I have seen people in airports devastated by a delay significant enough for them to miss their ship. I have seen people borrowing clothes on an Atlantic crossing because their luggage didn’t make it onto their plane, and there was no way to get their own clothes to them until a week later, when we hit the first port on the other side of the ocean—just in time for them to fly home. Both were probably avoidable. Neither of those disasters has ever happened to me, and I am pretty sure I can keep that record going.

For me, the aching body and the jet lag are all the stress I willingly accept as the price of travel, and my goal is to stay as clear of the anxieties as I possibly can, and laugh and count my blessings when I can’t,

I’ll discuss Corona Axiom 2 in a subsequent post, but I’ll give it to you here, since it builds on Axiom 1:

Axiom 2a:The mind is capable of magnifying small, solvable problems into huge, unsolvable ones.

Axiom 2b: The mind is also capable of diminishing huge problems into small, solvable ones.

The goal is to try to do more of B and less of A. I’ll share thoughts on that another time.