For authors, a new book is such a daunting process that the earliest stages, long before the first words of chapter one are put down, is a time of wary circling. You know the feeling–something interesting and unfamiliar catches your eye, and you move in, maybe just a little, to check it out more closely, maybe poke it with a stick to see if it moves.

You don’t know–you really just don’t know–what’s going to happen. Every year I must go through several dozen ideas for historical novels, some I think of on my own, but probably the majority suggested by fans and friends. Some ideas get abandoned quickly–not enough information for a historical novelist to go on, not enough interesting or appealing in the lives of the real-life characters, not enough of something else. Other ideas get put aside for another time. The circling begins with the third group, the ideas that won’t go away, the voices that say, “write about me!”

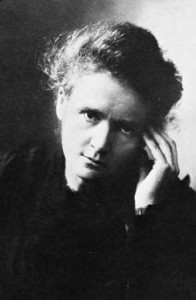

My bookshelves are full of biographies of women I haven’t written novels about and probably won’t: Cosima Liszt Von Bulow Wagner, Alma Schindler Mahler Gropius Werfel, Hypatia, Clara Schumann, Hadley Hemingway, Gertrude Caton Thompson, to name a few. Several are still possibilities: Ada Lovelace, Pauline Viardot, and Marie Curie spring to mind.

Marie Curie is the latest casualty of my circling. I read every biography of  her (four, if I recall) and even wrote fifty pages of a first draft before I ran into an obstacle I didn’t know how to handle. In my four novels to date the protagonists have always been characters of my invention through whose lives fascinating real-life characters come and go. I had some doubts about having a biographical character as the protagonist, but Curie’s life is just so amazing that I set my concerns aside.

her (four, if I recall) and even wrote fifty pages of a first draft before I ran into an obstacle I didn’t know how to handle. In my four novels to date the protagonists have always been characters of my invention through whose lives fascinating real-life characters come and go. I had some doubts about having a biographical character as the protagonist, but Curie’s life is just so amazing that I set my concerns aside.

Turns out that little muse fretting on my shoulder was right to be nervous. I have had to admit in the last week that a novel about Marie Curie just isn’t working.

In my first draft, I told the story from Marie’s point of view, as a third person narration. Here are the opening few sentences:

“Don’t look,” Manya Sklodowska whispered to herself as the first snow of the season thickened the air and stuck to the lawns of the Saxony Garden outside her classroom. She knew it was snowing even without looking, because the world sounded different, as if someone had picked up the edges of Warsaw in white paper and wrapped up a gift of silence.

At neat rows of desks, twelve-year-old girls in white-collared, blue serge uniforms squirmed. They’d been waiting for snow for all day, ever since the gray sky began to lower and the air took on the faint astringency of winter….

Okay, not bad for a first draft, but here’s the problem: I am describing something that happened that day to a real person. I had the biographies open in front of me and worked from them. I did a good job, in my estimation, in dramatizing a quite traumatic event involving a surprise visit by the superintendent of schools, but the problem was that the entire book would be no more than that. I would move on to the next few pages of her biography and dramatize that, and then the next, and in the end I would have told the story of her life, but not much more.

I learned something valuable from this–that I need to be able to make up the story. I get excited about inventing characters and putting them in situations where I don’t know what’s going to happen. That gets me up at six every morning ready to put fingers to the keys and continue the adventure. That wasn’t going to happen with Marie Curie, because there wasn’t a plausible fictional character I could create who would be alongside her, observing her but having her own life story too.

I decided to try a new approach, having multiple narrators from various stages of Marie’s life–her sister, her father, her first love, her husband, her fellow physicists, her students, her lover. Here is the same scene told from the point of view of Hela, who was in the same class as Marie:

“Don’t look!” My mouth forms words I don’t dare say aloud. The first snow of the year is falling. Nothing else thickens the air indoors this way, or makes the world outside go quite so silent.

I stare straight ahead at Mademoiselle Tupalska. Over her old-fashioned whalebone collar, old Tupsia has one of the meanest and ugliest faces I’ve ever seen. Her thick brows knit into one line, and her mouth turns down in furrows that make her chin look cut through like a marionette’s. She’s taking out her ruler now and laying it on the desk. After a few months of school, there’s no need to slap it in her palm to frighten us into obedience. Most of us know from experience the damage she can do with it.

Tupsia knows what I want–what every one of the girls in our white-collared blue serge uniforms wants–as we sit in our neat rows of desks reciting Russian verbs. We’ve been waiting for snow for all day. Now the tickle in my nostrils from a draft through a cracked window has a faint astringency like the witch hazel we put on our scrapes and scratches at home. I see the other girls trying not to squirm or let their eyes drift to the windows, where we could be making halos of our breath, or punctuating the condensation on the window with the tips of our noses. Old Tupsia will have none of that. She doesn’t care if it’s snowing. She only cares about these dusty old books. I bet she eats cardboard for breakfast.

I try not to giggle at the thought as I look sidelong at my sister Maria. She’s ten, a year younger than I am. Before she was advanced into my class, I was the youngest and the smartest, but Manya knows everything I do and a lot more besides. Math, history, literature, German, French, and catechism–she’s the best at all of them, even though she is a bit too chubby around the middle and has hair that never looks nice for more than a minute…

I kind of like this approach, but deep down I still don’t think I have solved the problem. I am still stuck with too little to create except phrasings. I love to write, and I find point of view one of the most fascinating aspects of fiction, and if someone said “we’ve just got to have a book about Marie Curie and we need it soon,” I would probably go forward. But no one is saying that, and I am very glad of it, because I have decided to put this project aside until I find a way around this problem, if there is one.

This is the first time this has happened to me. Usually I get inspired and plough through to successful completion of a novel. This was a really valuable lesson, to see that there is more to a historical novel than a great real-life story. Marie Curie supplied the plot and the characters, but she couldn’t supply the inspiration. But I can wait. If she wants her story told, she’ll find a way to get in touch.