I recently wrote a guest column for San Diego Jewish World, about my experiences writing in partnership with Michael Bart. Click “Read More” for the link to “Award Winning Author Tells the Story Behind the Story” and you’ll find it right here.

I recently wrote a guest column for San Diego Jewish World, about my experiences writing in partnership with Michael Bart. Click “Read More” for the link to “Award Winning Author Tells the Story Behind the Story” and you’ll find it right here.

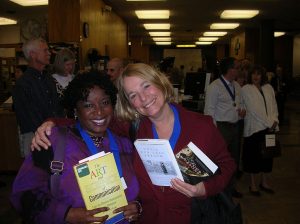

Sometimes a photo says it all. Here I am with my good friend Pamela Shekinah Perkins, who was writing her own book around the time I was debating whether to write UNTIL OUR LAST BREATH. Both our books came out roughly the same time, hers from Wiley  and Sons, entitled THE ART AND SCIENCE OF COMMUNICATION. She’s the one I acknowledged in the back of UNTIL OUR LAST BREATH as having “cajoled and challenged” me to take the leap as a writer that UNTIL OUR LAST BREATH required. She’s also the founder of the Human Communication Institute (www.hci-global.net) Think we’re glad to be friends? I am so proud of her.

and Sons, entitled THE ART AND SCIENCE OF COMMUNICATION. She’s the one I acknowledged in the back of UNTIL OUR LAST BREATH as having “cajoled and challenged” me to take the leap as a writer that UNTIL OUR LAST BREATH required. She’s also the founder of the Human Communication Institute (www.hci-global.net) Think we’re glad to be friends? I am so proud of her.

I’m spending the weekend up in the San Bernardino mountains working with my son, Ivan Corona, co-founder of Singularity Pictures (http://singularitypictures.com) on a video about UNTIL OUR LAST BREATH. That’s him, to the right, on location for another project. I have two equally strong professional identities, one as a writer and the other as an educator. I started teaching writing at the college level more than thirty years ago, and whatever I’m doing, I’m always tracking how it might be of use to students. I’m thinking now in terms of two contributions I can make through this video.

other as an educator. I started teaching writing at the college level more than thirty years ago, and whatever I’m doing, I’m always tracking how it might be of use to students. I’m thinking now in terms of two contributions I can make through this video.

First, I learned a great deal about writing by taking on the multi-year task of writing UNTIL OUR LAST BREATH, which was, among other things, my first book for an adult audience, my first full-length book, and my first experience working with someone else on a project where I was the writer. With content as interesting as that in UNTIL OUR LAST BREATH, it’s easy to overlook the other story of any book, which is how it came into existence–how a writer decides to take on a project and the initial decisions that have to be made once that decision is reached. Voice, point of view, interwoven narratives, and the different and occasionally conflicting demands of storytelling and historical accuracy are all things I know a lot more about as a result of writing UNTIL OUR LAST BREATH. I would like to share my perspectives as its author with high school and college students taking composition classes, as well as book groups or other audiences interested in writers and the writing process in general.

Second, as a result of a number of recent mandates, a great deal of effort is going into improving classroom instruction about the Holocaust. My new video project, “A WORLD ENTIRE,” is intended also to work as part of this new curriculum by providing background information about the Nazi occupation of Lithuania, the Vilna ghetto, and Jewish resistance. Talking about my own experiences writing about the Holocaust may also help students open up about the subject themselves. To make this project maximally useful for teachers across the curriculum, the video will conclude with about a dozen topics for class discussion or writing assignments.

My plan is to provide this roughly 20-30 minute video free of charge to schools and other groups interested in using it for non-profit, educational purposes. Ivan and I are also working on a short introduction to the video, which will be posted on YouTube. We’re still several months away from completion, so I hope you will check back for updates.

The cancellation of Herman Rosenblat’s Holocaust memoir, An Angel at the Fence, affected me personally because, if not for timely criticism of an early draft of Until Our Last Breath: A Holocaust Story of Love and Partisan Resistance, I might be facing something similar.

For those of you who may not be following this story, the pivotal event of Rosenblat’s book is being saved from starvation at Buchenwald by a girl who threw him apples over a fence. It’s a great love story, since many years later in New York he accidentally reconnected with the girl, and they eventually married. The problem is, he has now admitted he fabricated the story.

“So what?” some have asked. It’s a great, uplifting story, and memory is a tricky thing anyway. Deborah Lipstadt, author of Denying the Holocaust, has a succinct reply. “If you make up things about parts, you cast doubts on everything else,” Lipstadt recently told a reporter. “When you think of the survivors who meticulously tell their story and are so desperate for people to believe, then if they’re making stories up about this, how do you know if Anne Frank is true? How do you know Elie Wiesel is true?” She’s right. If someone wrote about being wounded at Midway but wasn’t actually there, no one would offer this as proof the battle never took place, but such denial happens all too easily with the Holocaust.

My research partner in Until Our Last Breath is the son of two Holocaust survivors, now deceased, whose role in the Jewish resistance against the Nazis in Vilna, Lithuania, forms an important part of the book. Jews who fought back are rarely the focus of Holocaust books, and I had more than enough documented facts to write the historical parts. The problem was we wanted a stronger narrative focus on this one particular couple’s story than the known or inferred facts allowed. Since this personal element of love and resistance distinguished this book from others, we initially made the decision that I could write as if they experienced certain things personally, when all we actually knew was that such things happened in places they were. After all, if what I wrote was generally true, all I was doing was making the book a better read, no?

No. And here’s where my praise of critics comes in. They did exactly what critics sometimes need to do: they panned the manuscript. A number of publishers turned it down out of discomfort with the fictional feel of parts of it. Good for them! I am genuinely grateful. Individuals close to the family gave even more pointed feedback about the need to stick to the facts. At that juncture I understood that, well-intentioned as we had been in including what only could have happened, the book fed the denial that Lipstadt warns against.

It would be nice if we’d gotten it right the first time. It’s never pleasant to be wrong about something in which one has invested a lot of time and effort, and I can attest to how tedious a major rewrite can be. This was a case, however, where what at first felt like a burden turned out to be a blessing. I wish for Mr. Rosenblat’s sake, that he had been similarly blessed.

I’ve worked with editors for many years and agents for a few, and I know the importance of having an open mind about something as personal and fraught with ego as one’s own writing. I know the down side also–that criticism can undermine fragile confidence and wreak havoc on a writer’s voice, but today I would like to say thank you to those who, by their willingness to give me feedback I haven’t always wanted to hear, have had a constructive influence on my writing.