“Laurel Corona brings Homer’s epic to life in this spectacular novel of the ancient world. Populated with a rich cast of characters—from Helen of Troy to Odysseus—this is a novel you won’t want to put down.”

Michelle MorAN, best-selling author of Nefertiti

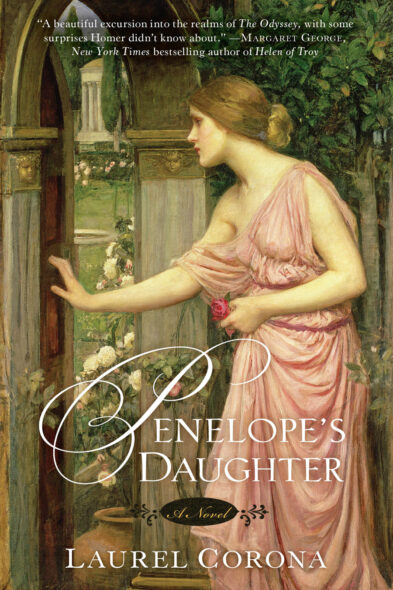

“A beautiful excursion into the realms of The Odyssey, with some surprises Homer didn’t know about.”

Margaret George, New York Times best-selling author of Helen of Troy

Over dinner one evening, after The Four Seasons was well on its way to publication, my partner and I started throwing around possibilities for the setting of my second novel. “How about Greece?” he said. “I’ve always wanted to go to Greece.”

My partner has been a great lover of Homer since he was young. “What about the Odyssey?” I asked, though I wasn’t enthusiastic about the idea at all. Most of what I remembered about Homer’s epics centered around bloodshed and fantasy, neither of which I have any interest in writing about. There was always Penelope, but I recalled not liking her much because she seemed to do nothing but cry, sleep, and ruin her weaving. All of my novels have female characters at the center, and the Penelope I remembered definitely wasn’t a heroine I would get along with very well as I wrote.

Then it came to me: what if, when Odysseus went off to the Trojan War, Penelope was pregnant with a daughter? Maybe that daughter could be the heroine. Almost immediately the Odyssey opened up in an entirely new way. I saw how the story might be told if the author were a woman. I envisioned it as a tale not about those who go off to war, but about those who stay behind. And I liked it better that way.

This novel is about girls having to grow up quickly in difficult environments. It’s about women gaining the skills needed to lead, negotiating the world of powerful men, and finding a way to thrive wherever they are. Penelope’s Daughter honors the real women of the Odyssey. If there is truth to the tale, they must have been half the population, even if they don’t show up in the story Homer wrote down.

Whereas Homer focuses on women mostly as threats and troublemakers, Penelope’s Daughter revels in the full range of things they are—mothers, daughters, slaves, weavers, high priestesses, queens. I came to see my story not as fiction at all, but as voices that are finally being heard. I hope you will enjoy what they have to say.

Synopsis

Odysseus goes off to the Trojan War unaware he has left his wife, Penelope, pregnant with her second child, a daughter she will name Xanthe. The teenaged queen of Ithaca is ill-prepared to manage the palace, and leaves Xanthe’s upbringing to servants and slaves, who introduce the young girl to life on the harsh but beautiful island. Xanthe’s world constricts as the years pass and her father does not return. By nineteen, when Penelope’s Daughter opens, Xanthe lives barricaded upstairs in the palace to keep her safe from the rapacious suitors who want to become king by murdering her brother and abducting her as their bride.

She passes the time by weaving the story of her life. The colors, textures, and designs that emerge on her loom serve as the framing device for each chapter in her narrative. We come to know Penelope, grown strong and wily by necessity, Telemachus, weak and self-impressed; Helen, sensual, fragile, and conflicted; Menelaus, broken and befuddled in the aftermath of war; Hermione, daughter of Helen and Menelaus, vengeful and bitter at her parents’ abandonment; Antinous and Eurymachus, predatory and unscrupulous in their plot to rule Ithaca; the swineherd Eumaeus; the servant Eurycleia; and the rest of the characters in Homer’s Odyssey through Xanthe’s visual and tactile artistry.

Most of all, we come to know Xanthe herself. As a child she is imaginative, brave, resourceful, and a bit too nosy and stubborn for her own good. In her teens, disguised for her protection, she comes to Sparta to live with her mother’s cousin, Helen of Troy. Now approaching forty, Helen is a complex, powerful combination of queen, priestess, goddess, and tormented soul. From her, Xanthe learns about womanhood through the pleasures of female friendship, the ecstasy of goddess worship, and the passion of her sexual awakening in the arms of the man she loves.

As she tells her story, from time to time, Xanthe’s attention is distracted by the sounds of battle and the cries of dying men. The tattered man who appeared in the hall of the palace the day before is her father, home after twenty years. A fight to the death has raged all day between Odysseus and the suitors. Xanthe stands with us before her loom, waiting to see whether a suitor she loathes, a brother she cannot respect, or a father who does not know she exists will be the one to decide her future.

Trade Reviews

“Born after her famous father, Odysseus, followed Menelaus to Troy to bring the city to its knees and Helen home to Sparta, Xanthe enjoyed an idyllic childhood. As the years passed, however, and Odysseus failed to return home to his kingdom of Ithaca, his wife, Penelope, was forced to endure an invasion of suitors hoping to win her hand and the kingdom. Still, Xanthe was not in personal danger until she reached age 11 and was deemed old enough to wed, by force if necessary. Sent to live with Penelope’s cousin, Xanthe spends her youth in hiding. There is no mention of a daughter in Homer’s epic poem, nor is there historical evidence that Odysseus and Penelope had a second child, but as the Greeks with whom Corona spoke during her extensive research said, ’If it makes a good story, why not?’ VERDICT Corona’s second historical novel (The Four Seasons) is indeed a good story—well researched, filled with strong, fully developed female characters, and an insightful look at the secret lives of the women of ancient Greece during an era that was pretty much all about the men. Sure to attract readers of Anita Diamant’s The Red Tent and Pilate’s Wife by Antoinette May.”

Library Journal, Jane Henriksen Baird, Anchorage P.L., AK

MEDIA REVIEWS

“…Laurel Corona’s new historical novel, ‘Penelope’s Daughter,’ provides some fascinating answers in a story that cleverly parallels Homer’s epic poem.”

THE NORTH COUNTY TIMES

“The Iliad, The Odyssey, and other Greek myths inform and enrich Corona’s (The Four Seasons) fanciful first-millennium tapestry of Xanthe, the daughter of Odysseus, king of the Cephallenians, born on the island of Ithaca to Penelope after Odysseus embarked on his mystical journey. With Penelope’s legendary husband missing for more than 20 years, Xanthe must come of age sheltered from those who would usurp the kingdom, force her and her mother into marriage, and kill her brother, the heir to the kingdom. As a precaution, her mother fakes Xanthe’s death and sends her to Sparta, where her cousin, the fabled Helen of Troy, can better protect her. There, Xanthe learns the mysteries of Bronze Age womanhood and witnesses an attempt on Helen’s life, possibly made by her own daughter, the bitter Hermione. Xanthe becomes involved with the son of the king of Phylos, but the gods decide she should return to Ithaca while there’s still hope that her father will return and peace may prevail. This variant and dreamy confection of Greek mythology and romance achieves, thanks to Xanthe’s first-person account, a great deal of intimacy.”

Publishers Weekly

“This novel revisits the story of the Trojan War and its aftermath. As it opens, the war has long ended, and the family of the missing Odysseus is still awaiting his return. Daughter Xanthe is left under the care of servants. She has barricaded herself in her room as a protection against unwanted suitors, passing the time by weaving. The story unfolds as she works at her loom, the designs serving as a framework to her tale. As Xanthe shares her history of ancient Greece, a complex picture emerges. Though the war has ended, the people of Ithaca are still immersed in a battle for their future. In Homer’s saga, women who once wept for their lost men are given the voice and power they deserve. In Corona’s tale, women turn a tragedy into opportunity, finding a way to thrive in a world full of men. Penelope’s Daughter provides new insight into the lives of Homer’s women while giving voice to the inventiveness, creativity, and ingenuity of all those left behind.”

BOOKLIST

“Readers may be charmed by this story and yet find it controversial.”

San Diego Jewish World

“Well-crafted adult modern literature about and for women.”

About.com

Years ago in high school I was forced to read the Iliad and/or the Odyssey… I retained nothing from the story though. Luckily for Homer, here comes Laurel Corona breathing new life into the age old tale, with her story of Penelope’s Daughter.

The Burton Review

“I honestly must say, I don’t know much about Greek Myths… but I really enjoyed reading Penelope’s Daughter.”

Marjojleinbookblog.blogspot.com

“If you are a fan of The Odyssey you are sure to enjoy the events that transpire in this book.”

The Maiden’s COurt

“This was my first read by Laurel Corona, but you can be bet I will be back for more! Penelope’s Daughter was one phenomenal book and I highly recommend it!”

Passages to the past

Combining romance, action and adventure, Penelope’s Daughter is a wonderful book crafted a talent that almost anyone would enjoy!

Coy M., Luxury Reading

AUTHOR REVIEWS

“Laurel Corona brings Homer’s epic to life in this spectacular novel of the ancient world. Populated with a rich cast of characters—from Helen of Troy to Odysseus—this is a novel you won’t want to put down.”

—Michelle Moran

best-selling author of Nefertiti

“A beautiful excursion into the realms of The Odyssey, with some surprises Homer didn’t know about.”

Margaret George, New York Times best-selling author of Helen of Troy

Q&A

What prompted you to write penelope’s daughter?

Actually, this book was a surprise. I was vacillating between two other ideas for novels, one set in pre-revolutionary France and another in medieval Iberia, but when the idea for Penelope’s Daughter came to me, I knew almost instantaneously that I would be putting all other ideas aside for a while. The Muse on this one was a tough taskmaster—more like a Harpy shrieking orders than a lovely thing with a lyre and a toga hovering discreetly nearby. I wrote the entire first draft in a little under eight months, which now seems completely crazy since I also have a full-time job. I started to feel as if there really was a Xanthe who had chosen me to tell her story and now she was busting loose with it. I could barely keep up with her!

You’re a professor of humanities, so did a longstanding interest in the classics affect your choice of subject matter?

Not really. I didn’t start by saying to myself, “I’d really like to set a novel in ancient Greece, because it’s one of my favorite subjects.” I have an abiding interest in women’s lives in past eras, so it is really their whispers I’m trying to hear. For me, it’s the story first, and I take whatever setting comes with it.

How did you research the book?

The research for this novel was different from my other books, for which a huge amount of research material was easily available. Athenian culture is the focus of most scholarship on ancient Greece, but Athens was very different from the earlier Mycenaean world in the Peloponnese. If the characters in the Odyssey were real people, they lived between the fall of the Mycenaean civilization and the rise of the Greek city-states, a period about which next to nothing is known. It seemed logical to conclude that Xanthe’s world would more closely resemble a past era in her own geographical neighborhood than a future one elsewhere in Greece, but this meant that most studies of classical Athens were of limited use. I relied more heavily on scholarship on Mycenae, while keeping in mind that I couldn’t even be sure about the relevance of that.

The single best source for me was the Odyssey itself. Even in situations where I knew Homer was wrong, I stuck with him as the authority. There was no road at the time between Pylos and Sparta, for example, and both Xanthe and Telemachus would have traveled not by chariot through the Taygetos Mountains, as Homer describes, but by boat around the southern end of the Peloponnese. In this and some other details, I decided it was important to go with the poem.

After I finished the first draft of Penelope’s Daughter, I went to the locations in Greece where the story was set. I spent time in Sparta (now Sparti), Pylos, and Kefalonia, which one respected group of scholars now believes is the site of ancient Ithaca. All of these places gave me geographic and sensual details that went into the revision of the book. Archaeological sites such as the partially reconstructed ruins of Knossos and Mycenae helped me picture what the palace at Sparta might have looked like, and the Heraklion and Athens museums gave me a sense for the kinds of ceremonial and decorative objects that would have been part of Xanthe’s world.

How closely does Penelope’s Daughter conform to the story in Homer? What did you use, what did you change, what did you invent?

I stuck very closely to the settings. The views and landscapes of Sparta, Pylos, and Kefalonia/Ithaca are just as I describe them. The vast majority of the characters in the novel are taken directly from the Odyssey, and their personalities are consistent with Homer. In cases where all I had was a name, such as Peisistratus, Hermione, and Helen’s three handmaidens, I invented personalities and fuller roles. The glossary for the book identifies which characters are from the poem and which are my creations.

I had to play around with the timing of some things in order to make the plot work. Though Homer is vague about the elapsed time between events, Odysseus was probably in hiding at Eumaeus’ pig farm by the time Telemachus returned from Pylos and Sparta. I needed time for Xanthe to weave her story before the battle with the suitors, so I added a few months. Likewise, although there are several versions of the story of Orestes’ murder of Clytemnestra and her lover, Aegisthus, Menelaus appears to have participated on his way home from Troy. It’s such a compelling part of the aftermath of the Trojan War that I wanted to use it, so I reset those events at the time Xanthe is in Sparta. There are a few other adjustments of that sort, none of which alters the original story in a significant way.

Readers who are interested in how I used the Odyssey might consider going back to read it for themselves. Maybe they will find themselves asking “where’s Xanthe?” in all the scenes where she should be, just as I do now.

How did what you read in the Odyssey shape your views of the characters?

Three characters in the Odyssey were revelations to me as their story unfolded. Penelope, quite frankly, doesn’t play well in the modern world. She seems so one-dimensional, a woman with nothing but her absent husband to give her substance and standing in the world. Sighing and weeping over her plight, and complaining ineffectively to her servants about the suitors gets a bit old even on first reading, and truly annoying when studying the book over and over, as I did. Today’s readers probably want to shake her by the shoulders and say, “Get on with it! Do something!”

Weaving the burial cloth to buy time is a nice touch, but it doesn’t really change the fact that Penelope is almost catatonically passive throughout Homer’s story. I have a hard time believing that anyone would let nineteen years pass without fighting back, especially when a son’s life is in jeopardy. I simply didn’t accept Homer’s version, and tried to picture how a smart and resourceful young woman living in this situation day after day, year after year, might really behave.

Helen was the second revelation. In Homer, she’s a ravishingly beautiful, remorseful troublemaker, but she had to be more complex than that. Replete with the feelings and perspectives gained from a lifetime of extraordinary experiences, she represents mature womanhood, glorious and full, actively shaping and influencing her world. Rescuing Helen from the margins of the Odyssey not only strengthens the plot of Penelope’s Daughter, but makes the point that many women of Helen’s era, supported by belief in powerful goddesses, must have felt about themselves the way I do about Helen.

Telemachus was another character who changed for me as a result of close, repeated readings of the Odyssey. Though Homer uses the stock phrases of oral poetry, making Telemachus seem “discreet” in thought and “godlike” in appearance, it’s hard to see how even Homer could find much of merit in his incessant whining both directly to the suitors and to others about what bullies they are. “I’m just a helpless little kid,” he seems to be saying, “but just you wait until I grow up!” Wait a minute—aren’t we in the twentieth year of Odysseus’ absence? Exactly what is Telemachus’ excuse?

I thought it was important early in the book to show Telemachus’ childhood temperament as leading toward a boastful but ineffectual adulthood, but once I set him loose in the plot, his character evolved more negatively than I had foreseen. Even Homer explains Telemachus’ uncharacteristic courage in the battle with the suitors as resulting from a spell cast by Athena, so I doubt even the bard himself would take too much issue with what I think is a very well deserved characterization.

Since Odysseus is the main character in Homer’s work and he might have greater name recognition, why didn’t you call the novel Odysseus’ Daughter?

Other than the awkward pronunciation? It’s important to think about such mundane things, but that isn’t really the reason. I was aware, from having asked a lot of people, that the Odyssey is less widely read than it used to be, and that many have only a passing familiarity with the story. Those who recall specifics mention the Cyclops or another of Odysseus’ adventures, and only a few easily remember there’s another story happening back home. If people don’t recall exactly who Odysseus is, changing the title wouldn’t help anyway. I decided to title the book in keeping with the story, and not worry about the issue of which parent was more famous.

I briefly thought about ways to include Odysseus in the main narrative of the book. The most promising approach seemed to be to give Xanthe inexplicable dreams that the reader could see as based in what was happening to her father—a nightmare about an escaping a one-eyed giant, or being the captive of a sorceress. I decided against this not just because it wouldn’t resonate anyway with readers unfamiliar with the story, but because it went completely against what I was trying to convey. The point is that he is not in Xanthe’s life. To have her dream of him puts him in it, and I thought it would take away from the force of a story that is meant to be solely about those left behind.

The plot can’t be resolved, however, without Odysseus coming home to triumph over the suitors. However, by that juncture, it was too late to build another character into the story unless I wanted to write a substantially longer book. I favor endings where characters seem poised to head off in a direction that readers can imagine for themselves, because the turning points in life are more interesting than the closures anyway. I chose one obvious and dramatic turning point, the battle with the suitors, and wrote an epilogue to provide an ending to the novel, if not the story.

How did you come up with the idea of having Xanthe’s weaving introduce each chapter?

The most dramatic way to frame the novel was with the pitched battle downstairs, and I knew I’d have to keep my female characters barricaded upstairs for that. I didn’t want Xanthe to wait it out passively, but to be doing something the whole time. I wanted to give her a platform by which to tell readers the story of her life, and weaving seemed the natural choice since it was such a big part of a woman’s world. Xanthe’s emotions are in turmoil, and I thought it would be natural for her to reject the idea of doing only what was expected of a young woman of marriageable age after all that has happened. No timid wedding trousseau for her, but rather a bold and defiant statement of who she is and where she’s been.

Were parts of the book more difficult to writer than others?

Yes. I truly do not like writing violent scenes, but occasionally they can’t be avoided. It gave me no pleasure to write about the aftermath of the battle with the suitors, and I was so glad when I was finished with it.

Another challenge for me was the treatment of the gods in the book. I wanted to respect the fact that my characters believed the gods were real—that they listened, they visited, they interceded. But I couldn’t have Hera, for example, clearly and unambiguously show up, because I don’t believe she’s real, and the story had to be plausible to me. I worked very hard to make the gods’ presence a matter of interpretation, so that readers could believe either that Hera dances with Xanthe or that Penelope only thinks that’s what she saw, or that the owl that keeps appearing is Athena or just an owl.

Another difficulty came about as a result of my decision to use a first person narration. Once I’d settled on the idea of using Xanthe’s weaving as part of the story, I had no choice in the matter, since she would obviously have to tell the reader her story herself. But a first-person narration meant that I had to write with the voice of someone who lived more than three millenia ago, and it was difficult to keep my own perspectives and vocabulary from taking over. Sometimes it was as simple as reminding myself that she couldn’t describe a gaze as “steely,” since there was no steel, or talk about units of time such as minutes or weeks. Other times I had to ask myself broader questions—could she really have thought this or said that, or done the things I have her do? If it’s in Penelope’s Daughter, I decided she could. What I took out are going to remain private, and somewhat embarrassing jokes.

Do you think you will visit the ancient world again for a novel?

I have no plans, but who knows what forgotten woman is out there looking for an author? I’m always listening for her.

Penelope’s Daughter: Ideas for Book Clubs

Send Me Your Book Club Ideas

If your book club adopts one of my novels, I would be delighted to set up a visit. If you are local to the San Diego area, I may be able to come in person, and for others, I am happy to chat by phone.

I’d love to hear your ideas! Write to me, lacauthor@gmail.com, to let me know what you did at your event and how it went! Send photos and I’ll post them on the site!

Some Fun Ideas for Your Book Club

- Serve olives, fresh fruit, and simple white cheese drizzled with honey. Get some Greek olive oil and serve pita or other bread to dip in it.

- Remember that this was a goddess-centered culture. If your book club is comfortable with the idea, have a “Release your Inner Goddess” theme and let participants surprise each other.

Interviews with Laurel

You may find ideas for book club discussion from these online interviews and guest blog posts: